COPENHAGEN, DENMARK—The diplomatic ice sheet between the United States and its Nordic allies has fractured deeper than ever before, as Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen issued a stern, unprecedented ultimatum to President Donald Trump on Sunday: “Stop the threats” against Greenland.

In a sharply worded statement that breaks with decades of diplomatic protocol between the NATO allies, Frederiksen categorically rejected President Trump’s renewed assertions that the U.S. “absolutely” needs the autonomous territory, warning that Washington has “no right to annex” any part of the Danish Kingdom.

The confrontation comes amid heightened global anxiety following the U.S. military’s lightning raid in Venezuela, a move that has left European capitals fearing that the White House’s new doctrine of “sovereign acquisition” might turn northward.

The Trigger: A Flag, A Post, and an Interview

The diplomatic firestorm was ignited by a one-two punch of provocative signaling from the Trump inner circle this weekend.

- The ‘SOON’ Post: On Saturday, Katie Miller, wife of Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, posted an image on X (formerly Twitter) depicting an American flag draped over the entirety of Greenland’s landmass. The caption consisted of a single, chilling word: “SOON.”

- The Atlantic Interview: Hours later, in a telephone interview with The Atlantic, President Trump doubled down on his long-standing ambition. “We do need Greenland, absolutely,” the President declared. “We need it for defense.” Crucially, when pressed on methods, he refused to rule out the use of “economic or military pressure” to secure the island, citing the recent success in Venezuela as proof of American resolve.

‘Disrespectful’ and Dangerous

Frederiksen’s response was immediate and fierce, signaling that Copenhagen views the latest rhetoric not as bluster, but as a genuine security threat.

“I need to say this very directly to the United States: It makes absolutely no sense to talk about it being necessary for the United States to take over Greenland,” Frederiksen stated. “I therefore strongly urge the United States to stop the threats against a historically close ally and against another country and another people who have very clearly stated that they are not for sale.”

Greenland’s Premier, Jens-Frederik Nielsen, joined the chorus of condemnation, labeling the social media post by Miller as “disrespectful” and a violation of the mutual respect that should define relations between allies. “Relations between nations… are not built on symbolic gestures that disregard our status and our rights,” Nielsen wrote.

The Venezuela Shadow

The timing of the dispute has amplified the alarm. The recent U.S. capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has fundamentally altered the geopolitical calculus, with allies no longer certain that Washington will respect traditional boundaries of sovereignty.

Defense analysts suggest that the appointment of Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry as a “Special Envoy to Greenland” in December was the first concrete step in an operational plan. Landry has openly thanked the President for the opportunity to “make Greenland a part of the U.S.,” a mandate that Denmark formally rejects.

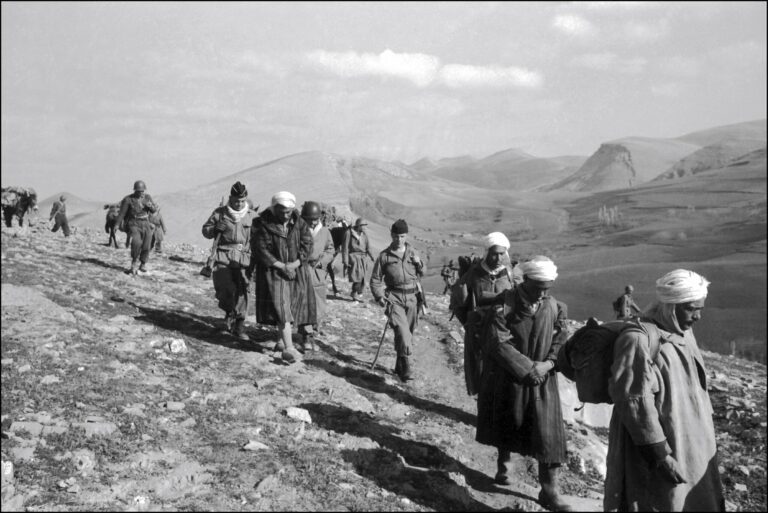

The Arctic Stakes

For the Trump administration, the acquisition of Greenland is viewed as a strategic necessity to counter Russian and Chinese influence in the Arctic and secure vast deposits of rare earth minerals. The island already hosts the Pituffik Space Base, the U.S. military’s northernmost installation.

However, for Denmark and the 57,000 people of Greenland, the island is not a strategic asset to be traded, but a home. As the “America First” foreign policy takes an increasingly expansionist turn, the Kingdom of Denmark finds itself on the front line of a new kind of cold war—one fought not against enemies, but against its oldest ally.