UCLA scientists have found that human stem cells can be genetically engineered into “warrior” cells that fight HIV and the new cells can attack HIV-infected cells inside a living creature.

The breakthrough discovery is hoped to be the first step towards a treatment that can eradicate HIV from an infected patient.

Much HIV research focuses on vaccines or drugs that slow the virus’s progress – but this new technique could offer hope of a “cure”.

The study, published April 12 in the journal PLoS Pathogens, demonstrates for the first time that engineering stem cells to form immune cells that target HIV is effective in suppressing the virus in living tissues.

“We believe that this study lays the groundwork for the potential use of this type of an approach in combating HIV infection in infected individuals, in hopes of eradicating the virus from the body,” said lead researcher Scott G. Kitchen.

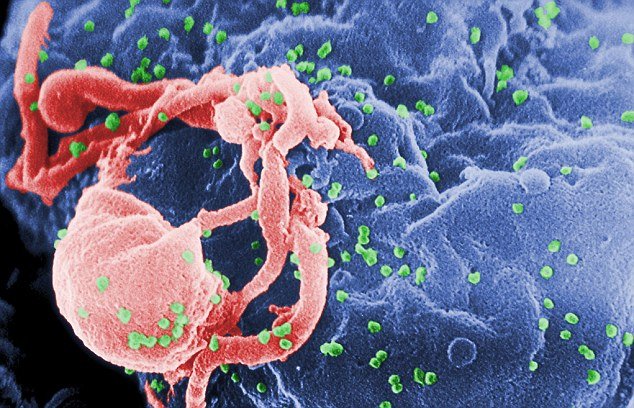

The scientists took CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes – the “killer” T cells that help fight infection – from an HIV-infected individual and identified the molecule which guides the T cell in recognizing and killing HIV-infected cells.

However, these T cells, while able to destroy HIV-infected cells, do not exist in great enough quantities to clear the virus from the body.

So the researchers cloned the receptor and used this to genetically engineer human blood stem cells. They then placed the engineered stem cells into human thymus tissue that had been implanted in mice, allowing them to study the reaction in a living organism.

The engineered stem cells developed into a large population of mature, multi-functional HIV-specific cells that could specifically target cells containing HIV proteins.

The researchers also discovered that HIV-specific T cell receptors have to be matched to an individual in much the same way an organ is matched to a transplant patient.

In this current study, the researchers similarly engineered human blood stem cells and found that they can form mature T cells that can attack HIV in tissues where the virus resides and replicates.

They did so by using a surrogate model, the humanized mouse, in which HIV infection closely resembles the disease and its progression in humans.

In a series of tests on the mice’s peripheral blood, plasma and organs conducted two weeks and six weeks after introducing the engineered cells, the researchers found that the number of CD4 “helper” T cells – which become depleted as a result of HIV infection – increased, while levels of HIV in the blood decreased.

“We believe that this is the first step in developing a more aggressive approach in correcting the defects in the human T cell responses that allow HIV to persist in infected people,” Scott G. Kitchen said.