Scientists say life expectancy is written into our DNA and could be seen from the day we are born.

They have found a way to predict how long someone will live – by measuring their genes as a baby

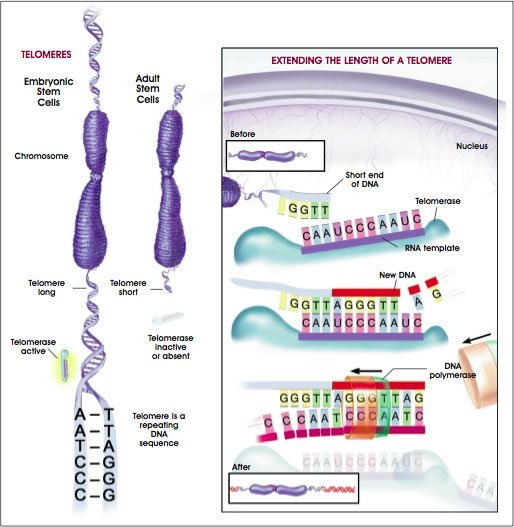

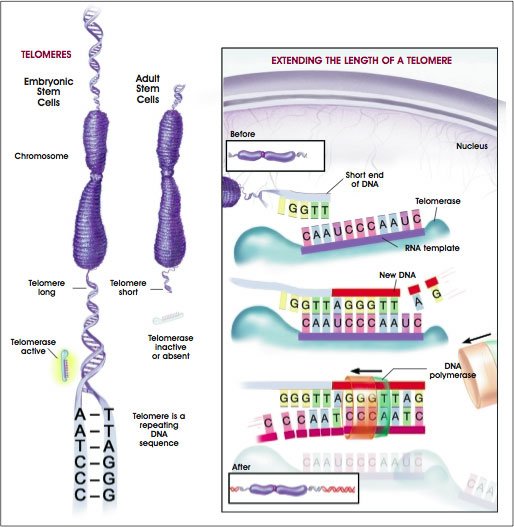

It all depends on the length of the telomeres, which are described as “acting like the plastic ends on shoelaces” to protect chromosomes from wear and tear.

Telomeres are being studied extensively – and are thought to hold the key to ageing.

The longer your telomeres, the longer you will live – dependent, of course, on not dying accidentally, from disease or from lifestyle factors.

It was known they could be shortened by life choices, including smoking and stress. But this is the first indication that our lifespan might be predetermined from birth.

In the future, tests may allow people to know their expected lifespan from a very early age – if they want to.

Professor Pat Monaghan, who led the Glasgow University study, said: “The results of this research show that what happens in our bodies in early life is very important.

“It is not understood why there are variations of telomere length but if you had a choice, you would want to be born with longer telomeres.

“If you were to test this, I don’t think anyone would want to know – it would just make you miserable. But it must be remembered that how you live has a big effect. This isn’t quite a case of nature overtaking nurture.”

The study – which used zebra finches, one of Australia’s most common bird species – is the first to measure telomere lengths at regular intervals through an entire life. With people, it is usually only the elderly who are studied because of the timescales involved.

Blood cell samples were taken from 99 finches, starting when they were 25 days old.

The results exceeded even the researchers’ expectations. The birds with the shortest telomeres did tend to die first – from as early as seven months after the start of the trial.

But one bird in the group with the longest telomeres survived to almost nine years old.

Professor Monaghan said: “These birds were dying of natural causes. There were no predators, no diseases and no accidental deaths. This was showing their capacity for long life.”

The results hold huge implications for humans, whose telomeres work in the same way.

Telomeres are important because they stop DNA from unraveling, but they begin shortening from the moment we are conceived.

The longer they are, the better for an individual because when they get too short, they stop working.

DNA is then no longer protected and errors begin to creep in when cells divide. When this happens – usually in middle age – the skin begins to sag and the immune system becomes less efficient. Faulty cells also lead to a growing risk of conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

The university’s institute of biodiversity, animal health and comparative medicine has published its groundbreaking research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

In the next stage of their research, the Glasgow scientists will look at what causes telomeres to shorten – including inherited and environmental factors – to make it possible to predict life expectancy more accurately.