Home Tags Posts tagged with "hiv"

hiv

According to a new study published in Science Translational Medicine, a 10th of children have a “monkey-like” immune system that stops them developing AIDS.

The study found the children’s immune systems were “keeping calm”, which prevented them being wiped out.

An untreated HIV infection will kill 60% of children within two and a half years, but the equivalent infection in monkeys is not fatal.

The findings could lead to new immune-based therapies for HIV infection.

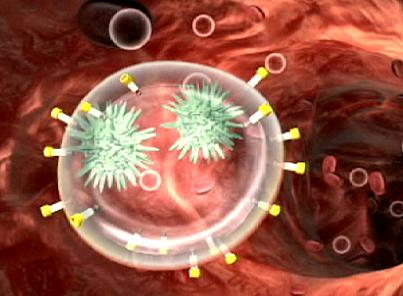

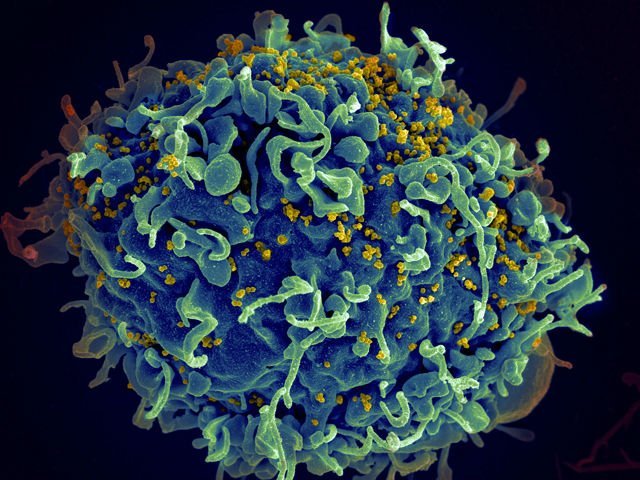

HIV eventually wipes out the immune system, leaving the body vulnerable to other infections, what is known as acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

The researchers analyzed the blood of 170 children from South Africa who had HIV, had never had antiretroviral therapy and yet had not developed AIDS.

Tests showed they had tens of thousands of human immunodeficiency viruses in every milliliter of their blood.

This would normally send their immune system into overdrive, trying to fight the infection, or simply make them seriously ill, but neither had happened.

Counter-intuitively, not attacking the virus seems to save the immune system.

HIV kills white blood cells – the warriors of the immune system.

When the body’s defenses go into overdrive, even more of them can be killed by chronic levels of inflammation.

For scientists, the way the 10% of children cope with the virus has striking similarities to the way more than 40 non-human primate species cope with simian immunodeficiency virus or SIV.

They have had hundreds of thousands of years to evolve ways to tackle the infection.

This defense against AIDS is almost unique to children.

Adult humans’ immune systems tend to go all-out to finish off the virus in a campaign that nearly always ends in failure.

Children have a relatively tolerant immune system, which becomes more aggressive in adulthood – chickenpox, for example, is far more severe in adults due to the way the immune system reacts.

This does mean that as the protected children age and their immune system matures, there is a risk of them developing AIDS.

Some do, some remain AIDS-free.

People with HIV can have normal life-expectancy if they have access to antiretroviral drugs.

But their super-heated immune system never returns to normal, and they face greater risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer and dementia.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), everyone who has HIV should be offered antiretroviral drugs as soon as possible after diagnosis.

The health agency’s latest policy removes previous limits suggesting patients wait until the disease progresses.

The WHO has also recommended people at risk of HIV be given the drugs to help prevent the infection taking hold.

UNAIDS said these changes could help avert 21 million AIDS-related deaths and 28 million new infections by 2030.

The recommendations increase the number of people with HIV eligible for ARVs from 28 million to 37 million across the world.

The challenge globally will be making sure everyone has access to them and the funds are in place to pay for such a huge extension in treatment. Only 15 million people currently get the drugs.

Michel Sidibe, of UNAIDS, added: “Everybody living with HIV has the right to life-saving treatment. The new guidelines are a very important steps towards ensuring that all people living with HIV have immediate access to antiretroviral treatment.”

The WHO announcement comes after extensive research into the issue.

A US National Institutes of Health study due to run until 2016 was stopped early after an interim analysis found giving treatment straight after diagnosis cut deaths and complications, such as kidney or liver disease, by half.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced that smart syringes that break after one use should be used for injections by 2020.

Reusing syringes leads to more than two million people being infected with diseases including HIV and hepatitis each year.

The new needles are more expensive, but the WHO says the switch would be cheaper than treating the diseases.

More than 16 billion injections are administered annually.

Normal syringes can be used again and again.

The smart ones prevent the plunger being pulled back after an injection or retract the needle so it cannot be used again.

This is also a problem in rich Western countries.

An outbreak of hepatitis C in Nevada was traced back to a doctor who used the same syringe to give anaesthetic to multiple patients.

Standard syringes cost between 2 cents and 4 cents. The smart syringes cost between 4 and 6 cents.

The WHO describes it as a “small increase”. However, the tiny difference in the price of one needle becomes huge when it is scaled up to 16 billion injections.

The health agency is also calling for sheathed needles that prevent doctors accidentally pricking their fingers.

This has happened many times during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

They would treble the cost of the syringes and the WHO says these would have to be introduced “progressively”.

The WHO is calling on industry to expand production and find ways of reducing the cost of the safer needles.

But the measure will not be the end of the typical syringe.

They will be needed for needle exchange programs for drug users as well as in some treatments in which multiple medicines are mixed in the syringe before being injected.

[youtube dBx2ezV2w5I 650]

According to a major scientific study, HIV is evolving into a milder form, becoming less deadly and less infectious.

The research team at the University of Oxford shows the virus is being “watered down” as it adapts to our immune systems.

It said it was taking longer for HIV infection to cause AIDS and that the changes in the virus may help efforts to contain the pandemic.

Some virologists suggest the virus may eventually become “almost harmless” as it continues to evolve.

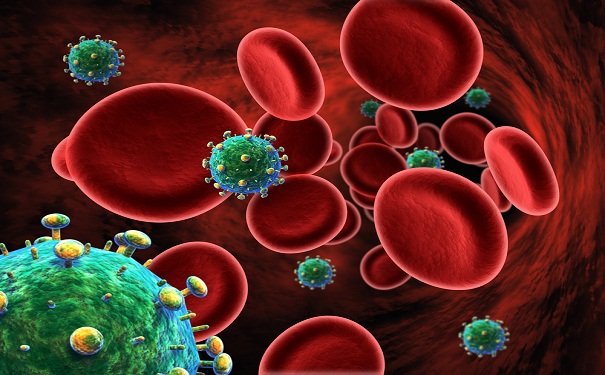

More than 35 million people around the world are infected with HIV and inside their bodies a devastating battle takes place between the immune system and the virus.

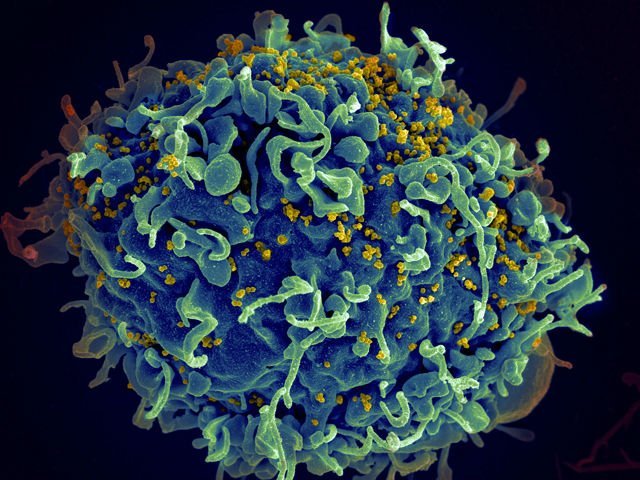

HIV is a master of disguise. It rapidly and effortlessly mutates to evade and adapt to the immune system.

However, every so often HIV infects someone with a particularly effective immune system.

“[Then] the virus is trapped between a rock and hard place, it can get flattened or make a change to survive and if it has to change then it will come with a cost,” said Prof. Philip Goulder, from the University of Oxford.

The “cost” is a reduced ability to replicate, which in turn makes the virus less infectious and means it takes longer to cause AIDS.

This weakened virus is then spread to other people and a slow cycle of “watering-down” HIV begins.

The team showed this process happening in Africa by comparing Botswana, which has had an HIV problem for a long time, and South Africa where HIV arrived a decade later.

The findings in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences also suggested anti-retroviral drugs were forcing HIV to evolve into milder forms.

It showed the drugs would primarily target the nastiest versions of HIV and encourage the milder ones to thrive.

The group did caution that even a watered-down version of HIV was still dangerous and could cause AIDS.

HIV originally came from apes or monkeys, in which it is frequently a minor infection.

According to an international team of scientists said, the origin of the AIDS pandemic has been traced to the 1920s in the city of Kinshasa, in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

They say a “perfect storm” of population growth, s** and railways allowed HIV to spread.

A feat of viral archaeology was used to find the pandemic’s origin, the team report in the journal Science.

They used archived samples of HIV’s genetic code to trace its source, with evidence pointing to 1920s Kinshasa.

Their report says a roaring s** trade, rapid population growth and unsterilized needles used in health clinics probably spread the virus.

Meanwhile Belgium-backed railways had one million people flowing through the city each year, taking the virus to neighboring regions.

Experts said it was a fascinating insight into the start of the pandemic.

The origin of the AIDS pandemic has been traced to the 1920s in the city of Kinshasa

HIV came to global attention in the 1980s and has infected nearly 75 million people.

It has a much longer history in Africa, but where the pandemic started has remained the source of considerable debate.

A team at the University of Oxford and the University of Leuven, in Belgium, tried to reconstruct HIV’s “family tree” and find out where its oldest ancestors came from.

The research group analyzed mutations in HIV’s genetic code.

By reading those mutational marks, the research team rebuilt the family tree and traced its roots.

HIV is a mutated version of a chimpanzee virus, known as simian immunodeficiency virus, which probably made the species-jump through contact with infected blood while handling bush meat.

The virus made the jump on multiple occasions. One event led to HIV-1 subgroup O which affects tens of thousands in Cameroon.

Yet only one cross-species jump, HIV-1 subgroup M, went on to infect millions of people across every country in the world.

The answer to why this happened lies in the era of black and white film and the tail-end of the European empires.

In the 1920s, Kinshasa (called Leopoldville until 1966) was part of the Belgian Congo.

Large numbers of male laborers were drawn to the city, distorting the gender balance until men outnumbered women two to one, eventually leading to a roaring s** trade.

Around one million people were using Kinshasa’s railways by the end of the 1940s.

The virus spread, with neighboring Brazzaville and the mining province, Katanga, rapidly hit.

Those “perfect storm” conditions lasted just a few decades in Kinshasa, but by the time they ended the virus was already starting to spread around the world.

[youtube yUUlMVB751Y 650]

Doctors treating a HIV-infected baby in Milan, Italy, say that giving drugs within hours of infection is not a cure.

The newborn infant cleared the virus from their bloodstream, but HIV re-emerged soon after antiretroviral treatment stopped.

Doctors had hoped rapid treatment would might prevent HIV becoming established in the body.

Experts said there was “still some way to go” before a cure was found.

Drug treatments have come a long way since HIV came to global attention in the 1980s and infection is no longer a death sentence.

However, antiretrovirals merely clear the virus from the bloodstream leaving reservoirs of HIV in other organs untouched.

The hope was that acting before the reservoirs formed would be an effective cure.

Drug treatments have come a long way since HIV came to global attention in the 1980s and infection is no longer a death sentence

Doctors at the University of Milan and the Don Gnocchi Foundation in the city have reported a case, in the Lancet medical journal, of a baby born to a mother with HIV in 2009.

Drug treatment started shortly after birth and the virus rapidly disappeared from the bloodstream. HIV was undetectable at the age of three.

The doctors said: “In view of these results, and recent reports of apparent cure of HIV infection, and in agreement with the mother, we stopped antiretroviral therapy.”

For one week everything seemed fine, but in the second week, after treatment stopped, the virus had returned.

In July 2014, a baby girl in the US born with HIV and believed cured after very early treatment was found to still harbor the virus.

Doctors said tests on the four-year-old child from Mississippi indicated she was no longer in remission.

The Mississippi girl had appeared free of HIV as recently as March, without receiving treatment for nearly two years.

Only one person has been “cured” of HIV.

In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown received a bone marrow transplant from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that resists HIV.

Timothy Ray Brown has shown no signs of infection for more than five years.

According to a new study, the rate of HIV infections diagnosed in the US has fallen by a third over the past decade.

After examining cases from all 50 states, the study found that the diagnosis rate fell to 16.1 per 100,000 people in 2011 from 24.1 in 2002.

Experts celebrated the findings as a hopeful sign that the AIDS epidemic may be slowing in the US.

However, there was a rise in new cases of HIV among gay and bis**ual men aged under 24 and over 45.

HIV is the virus that causes AIDS, a disease which destroys the immune system.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 35 million people globally have the virus. More than 1 million people in the US are thought to be infected, with 18% unaware of their infections.

From 2002 to 2011, 493,372 people were diagnosed with HIV in the US, researchers said.

The rate of HIV infections diagnosed in the US has fallen by a third over the past decade

As well as an overall decline, declines were also seen in the rates for men, women, whites, blacks, Hispanics, heteros**uals, injection drug users and most age groups.

Researchers said the only group in which diagnoses increased was gay and bis**ual men.

“Among men who have s** with men, unprotected risk behaviors in the presence of high prevalence and unsuppressed viral load may continue to drive HIV transmission,” the report said.

The study also found diagnosis rates dropped even as the amount of testing rose.

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended routine HIV testing for all Americans aged 13 to 64.

The percentage of adults ever tested for HIV increased from 37% in 2000 to 45% in 2010, according to CDC data.

Although experts say reasons for the US decline in infections are unknown, it is in line with a global downturn in the AIDS epidemic.

Last week, the UN said that there were 2.1 million new HIV infections worldwide in 2013, down 38% from 2001.

The study was released online by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) ahead of the International AIDS Conference that started in Melbourne, Australia, on Sunday.

According to new research, early HIV treatment may not cure the virus as it can rapidly form invulnerable strongholds in the body.

A baby was thought to have been cured with treatment hours after birth, but the virus emerged years later.

Monkey research, published in the journal Nature, suggests untouchable “viral reservoirs” form even before HIV can be detected in the blood.

Experts described it as a “sobering” and “striking” finding.

Reservoirs of HIV in the gut and brain tissue are the massive obstacle in the way of a cure.

Remarkable progress in developing antiretroviral drugs means HIV can be kept in check in the bloodstream and patients have a near-normal life expectancy.

But if the drugs stop, the virus will emerge from its reservoirs.

Early HIV treatment may not cure the virus as it can rapidly form invulnerable strongholds in the body

International research is focused on flushing the virus out of its reservoirs, but there had been hope that early treatment could prevent them forming in the first place.

In the study, rhesus monkeys were infected with the monkey equivalent of HIV – simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV).

The monkeys were then given antiretroviral drugs as early as three days or as late as two weeks after infection.

Treatment stopped after six months, but the virus re-emerged irrespective of how quickly antiretroviral treatment started.

It showed that viral reservoirs formed incredibly early in the course of the infection.

Dan Barouch, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, said: “Our data show that in this animal model, the viral reservoir was seeded substantially earlier after infection than was previously recognized.

“We found that the reservoir was established in tissues during the first few days of infection, before the virus was even detected in the blood.”

It had been believed a baby girl born with HIV had been cured after very early treatment.

The “Mississippi baby” was given HIV drugs for the first 18 months of life, but then they were stopped.

Initially the virus did not return and there was hope she had been effectively cured.

But last week it was announced that the girl, now four years old, was no longer in remission after nearly two years off the drugs.

“The unfortunate news of the virus rebounding in this child further emphasizes the need to understand the early and refractory viral reservoir that is established very quickly following HIV infection in humans,” Prof. Dan Barouch added.

Kai Deng and Robert Siliciano, of the School of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Maryland, commented: “These data indicate that the viral reservoir could be seeded substantially earlier than previously assumed, a sobering finding that poses additional hurdles to HIV eradication efforts.

“Although early treatment may not prevent reservoir seeding, it has been consistently shown to reduce the size of the reservoir.”

They highlighted significant differences between these experiments and the human HIV infection, but concluded that the findings “suggest new approaches in addition to early treatment will be necessary to eradicate HIV infection”.

According to a report by the United Nations AIDS agency, there is a chance the AIDS epidemic can be brought under control by 2030.

It said the number of new HIV infections and deaths from AIDS were both falling.

However, it called for far more international effort as the “current pace cannot end the epidemic”.

And charity Medecins Sans Frontieres warned most of those in need of HIV drugs still had no access to them.

The report showed that 35 million people around the world were living with HIV.

There were 2.1 million new cases in 2013 – 38% less than the 3.4 million figure in 2001.

AIDS-related deaths have fallen by a fifth in the past three years, standing at 1.5 million a year. South Africa and Ethiopia have particularly improved.

UNAIDS report said the number of new HIV infections and deaths from AIDS were both falling

Many factors contribute to the improving picture, including increased access to drugs. There has even been a doubling in the number of men opting for circumcision to reduce the risk of spreading or contracting HIV.

While some things are improving, the picture is far from rosy.

Fewer than four in 10 people with HIV are getting life-saving antiretroviral therapy.

And just 15 countries account for three-quarters of all new HIV infections.

The report said: “There have been more achievements in the past five years than in the preceding 23 years.

“There is evidence about what works and where the obstacles remain, more than ever before, there is hope that ending Aids is possible.

“However, a business-as-usual approach or simply sustaining the Aids response at its current pace cannot end the epidemic.”

Michel Sidibe, the executive director of UNAIDS, added: “If we accelerate all HIV scale-up by 2020, we will be on track to end the epidemic by 2030, if not, we risk significantly increasing the time it would take – adding a decade, if not more.”

Dr. Jennifer Cohn, the medical director for Medecins Sans Frontieres’ access campaign, said: “Providing life-saving HIV treatment to nearly 12 million people in the developing world is a significant achievement, but more than half of people in need still do not have access.”

In Nigeria, 80% of people do not have access to treatment.

Dr. Jennifer Cohn added: “We need to make sure no-one is left behind – and yet, in many of the countries where MSF works we’re seeing low rates of treatment coverage, especially in areas of low HIV prevalence and areas of conflict.

“In some countries, people are being started on treatment too late to save their lives, and pregnant women aren’t getting the early support they need.”

[youtube YwUmdpUIoW8 650]

A Mississippi girl born with HIV and believed cured after very early treatment has now been found to still harbor the virus.

Tests last week on the 4-year-old child indicate she is no longer in remission, say doctors.

She had appeared free of HIV as recently as March, without receiving treatment for nearly two years.

The news represents a setback for hopes that very early treatment of drugs may reverse permanent infection.

The Mississippi girl had appeared free of HIV as recently as March, without receiving treatment for nearly two years

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told US media the new results were “obviously disappointing” and had possible implications on an upcoming federal HIV study.

“We’re going to take a good hard look at the study and see if it needs any modifications,” he said.

The Mississippi baby did not receive any pre-natal HIV care prior to birth.

Because of a greater risk of infection, she was started on a powerful HIV treatment just hours after labor.

She continued to receive treatment until 18 months old, when doctors could not locate her. When she returned 10 months later, no sign of infection was evident though her mother had not given her HIV medication in the interim.

Repeated tests showed no detectable HIV virus until last week. Doctors do not yet know why the virus re-emerged.

A second child with HIV was given early treatment just hours after birth in Los Angeles in April 2013.

Subsequent tests indicate she completely cleared the virus, but that child also received ongoing treatment.

Only one adult is currently believed to have been cured of HIV.

In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown received a bone marrow transplant from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that resists HIV. He has shown no signs of infection for more than five years.

An international research team has shown how some cells in the body can repel attacks from HIV by starving the virus of the building blocks of life.

Viruses cannot replicate on their own; they must hijack other cells and turn them into virus production factories.

The study, published in Nature Immunology, showed how some parts of the immune system destroy their own raw materials, stopping HIV.

It is uncertain whether this could be used in therapy, experts caution.

HIV attacks the immune system and can weaken the body’s defenses to the point that everyday infections become fatal.

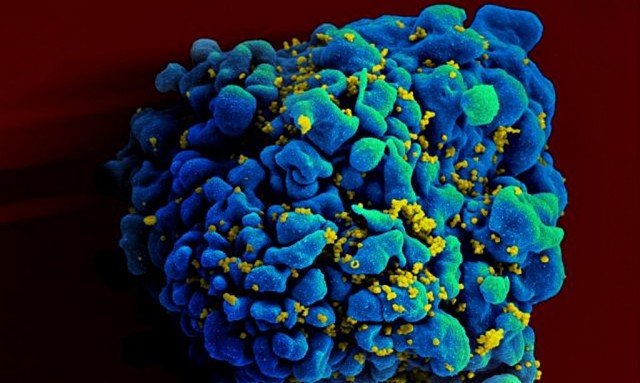

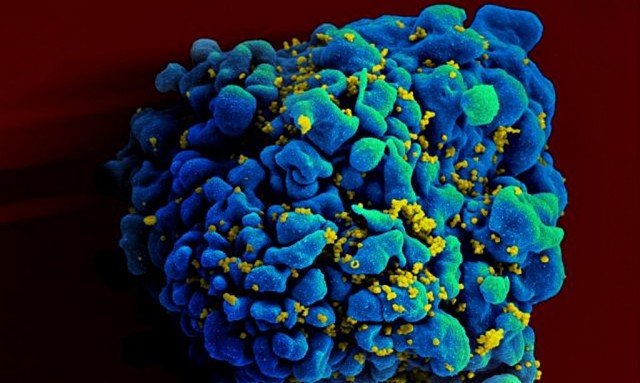

However, not all parts of the immune system become subverted to the virus’ cause. Macrophages and dendritic cells, which have important roles in orchestrating the immune response, seem to be more resistant.

In 2011, researchers identified the protein SAMHD1 as being a critical part of this resistance. Now scientists believe they know how it works.

The scientists have shown that SAMHD1 breaks down the building blocks of DNA. So if a cell needs to make a copy of itself it will have a pool of these building blocks – deoxynucleoside triphosphates or dNTPs – which make the new copies of the DNA. However, they can also be used by viruses.

The study, by an international team of researchers, showed that SAMHD1 lowered the levels of dNTPs below that needed to build viral DNA and prevented infection. When they removed SAMHD1 then those cells had higher levels of dNTPs and were infected by HIV.

The report said: “By depleting the pool of available dNTPs, SAMHD1 effectively starves the virus of a building block that is central to its replication strategy.”

HIV attacks the immune system and can weaken the body's defenses to the point that everyday infections become fatal

It is possible for macrophages and dendritic cells to produce SAMHD1 as they are “mature cells” which do not go on to produce new cells.

Prof. Baek Kim, one of the researchers from the University of Rochester Medical Center, said: “It makes sense that a mechanism like this is active in macrophages.

“Macrophages literally eat up dangerous organisms, and you don’t want those organisms to have available the cellular machinery needed to replicate and macrophages themselves don’t need it, because they don’t replicate.

“So macrophages have SAMHD1 to get rid of the raw material those organisms need to copy themselves. It’s a great host defense.”

Dr. Jonathan Stoye, virologist at the Medical Research Council National Institute of Medical Research, was part of the team which determined the chemical structure of SAMHD1 last year and predicted that it would attack the dNTPs.

“We hypothesized that it works in this fashion and the paper tells us we were right. It is depleting cells of these dNTPs, in cells which are not proliferating (dividing).”

However, some cells do need to divide to boost numbers as part of the immune defence. Such as CD4 cells which are the prime target for HIV infection.

“Cells which are proliferating would be in trouble if we took dNTPs away,” Dr. Jonathan Stoye said.

He added: “How we can use the anti-retroviral action of this protein is not clear to me.”