Until now, the regulation of health apps has more or less been left in the hands of the tech firms creating and selling them, but news from the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) this week indicated that they have reached a decision on the future of health app regulation.

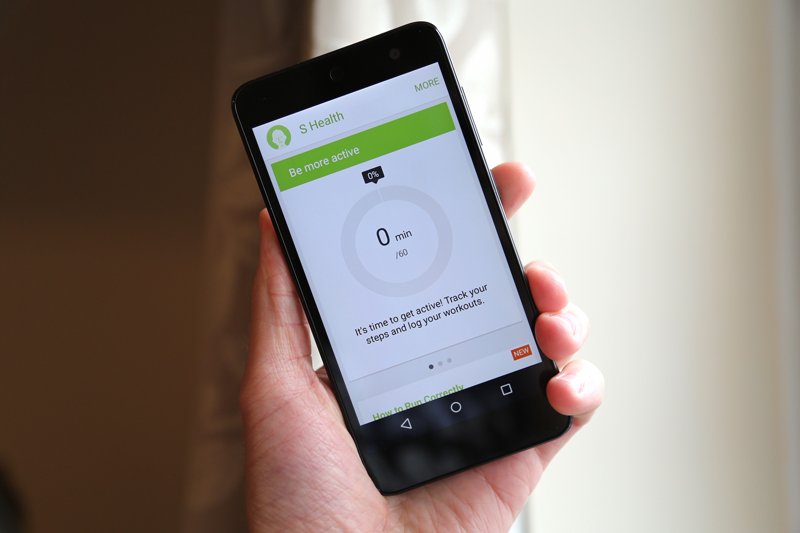

Health apps are undoubtedly incredibly useful, allowing patients to monitor basic statistics such as their calorific intake, their heart rate and their blood pressure without having to visit a doctor’s surgery or clinic. There has, however, been a degree of uncertainty regarding the legitimacy of the results given and the degree to which patients could rely on the information in terms of making their own decisions on treatment.

The final guidance recently issued by the FDA not only drew a line separating useful and harmless apps from those which might be more problematic, it also left the people responsible for developing health apps thanking their lucky stars at the approach being taken.

The guidelines unveiled confirmed the fact that the FDA plans to adopt a light touch approach to the regulation of most health apps, also known as medical device data systems (MDDS), as well as the specific software which is used to transmit the data collected to and from a specific medical device, such as a blood sugar meter.

The FDA released a statement which confirmed the scope of apps they had decided to place outside the reach of regulation:

“This guidance confirms our intention to not enforce regulations for technologies that receive, transmit, store, or display data from medical devices. We hope that finalization of this policy will create an impetus for the development of new technologies to better use and display this data.”

The caveat which the FDA attaches to this approach is that regulation can be maintained at a minimal level as long as the apps in question don’t represent a risk to the health of a patient in the event of a malfunction. Since the vast majority of such apps concentrate on the collating, sharing and collection of statistical information, as opposed to anything more in depth, they will not be affected by any intervention of the part of the FDA. The apps which might find themselves attracting the attention of regulators include those which, in the words of the FDA “….transform a mobile platform into a regulated medical device by using attachments, display screens, sensors, or other such methods”

Until now, the concern that some patients might be misled by health apps has centred upon those which go further than simply gathering information and, instead, offer diagnostic advice and even suggest treatments, areas which have previously been left in the hands of trained clinicians. The new regulatory regime will deal with such apps whilst giving developers a free hand to continue developing tools which gather information and monitor existing conditions, such as diabetes.

Experts within the field welcomed the news, feeling that it will promote innovation, push developers into new areas and help to create cutting edge apps able to greatly aid the field of preventative medicine.

Any issues around the clinical effectiveness of apps throws up the possibility that some patients, feeling they have been let down or misled, might wish to take legal action. A specialist team of medical negligence solicitors set out the legal situation in the following terms:

“Health app developers are unlikely to face medical negligence suits for a misdiagnosis, since there’s no doctor-patient relationship between the app developer, the provider and the patient. That’s one of the reasons patients should always communicate the doctor if they are using a health app, and check the accuracy of the information it provides.”

The changing landscape of health app regulation look set to be a hugely positive development for patients as a whole. The flexibility offered to developers will broaden the options on offer, and the lack of regulation required will assure patients that such apps are completely safe to use.