The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is warning doctors to be on the lookout for an untreatable multidrug-resistant “superbug” emerging in the U.S.

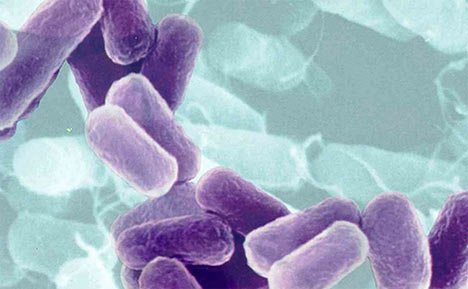

The “superbug” springs from a bacteria called Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriacea (CRE), 15 types of which have been seen in the U.S. in the last year. The unique bacteria can cause pneumonia, intestinal and urinary tract infections, and bloodstream infections.

In one outbreak at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, seven deaths were attributed to the “superbug” after a New York Woman who came to the hospital for a lung transplant while infected.

The victims included one 16-year-old boy.

The infections are associated with mortality rates of 40 to 50%.

The rise means health care providers must “act aggressively to prevent the emergence and spread of these unusual CRE organisms”, the CDC said.

“From the perspective of drug-resistant organisms, (CRE) is the most serious threat, the most serious challenge we face to patient safety,” Arjun Srinivasan, associate director for prevention of health care-associated infections at the CDC, told USA Today.

It can take over a year to be rid of CRE bacteria, with one study determining the average patient requiring 387 days for it to be out of their system.

“We’re working with state health departments to try to figure out how big a problem this is,” Arjun Srinivasan said, noting that his agency can pool whatever incidence data states collect.

“We’re still at a point where we can stop this thing. You can never eradicate CRE, but we can prevent the spread. … It’s a matter of summoning the will.”

Enterobacteriaceae flourish in the soil, water, and the human gut.

A “superbug”, CRE has a high level of resistance to antibiotics.

Disturbingly, the patients are not symptomatic, as the bug waits in the body until the immune system is compromised and an infection sets in.

The first known U.S. case was detected at a North Carolina hospital in 2001, and since then CRE’s have been detected in at least 41 other states.

Many cases still go unrecognized until is too late for the patient.

Since the first known case, at a North Carolina hospital, was reported in 2001, CREs have spread to at least 41 other states, according to the CDC. And many cases still go unrecognized, because it can be tough to do the proper laboratory analysis, particularly at smaller hospitals or nursing homes.

People diagnosed with a CRE infection usually get it after taking antibiotics and undergoing significant medical treatment for other conditions.

Also in the news last summer was an outbreak of CRE in eight patients – the largest outbreak in the U.S. so far.

None of the patients in the initial outbreak died.

The hospital was able to detect the outbreak early largely due to stringent surveillance protocols.

The CDC said most CRE cases were “isolated from patients who received overnight medical treatment outside of the United States”.

There are CDC guidelines to deal with the infection in the center’s 2012 CRE toolkit.

If you share a room with a person with a CRE infection you should be screened immediately.

Health care providers who treat infected patients should also be examined. They should not treat non-infected patients after treating infected ones.

Health care facilities must also be made aware of any CRE infected patients being transferred to their care.

Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae, or CRE, are bacteria that are unique in that they are resistant to most antibiotics. They typically live in the soil or water. Patients infected with the bacteria are typically not symptomatic, but can develop pneumonia, kidney and bladder infections, and bloodstream infectioins. They began appearing in the U.S. roughly ten years ago, and have since spread to at least 41 states. There is no effective treatment yet available for the bacteria, which can linger in the body more than a year, and mortality rates hover at 40 to 50%.