Market statistics show the French confectionery industry has been unaffected by the country’s financial problems and continues to grow at about 8% a year. And there is one particular treat that has always proved a favorite – ourson guimauve.

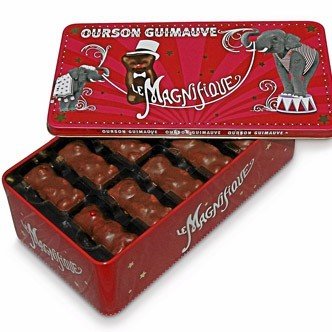

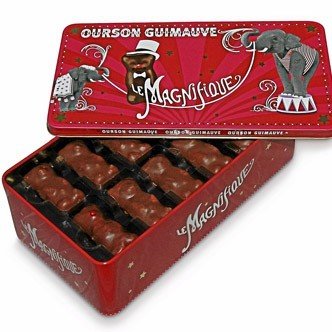

Oursons guimauve are small chocolate-covered marshmallow teddy bears (an ourson is a “bear cub”, guimauve is “marshmallow”). About the size of a Paris Metro ticket but considerably plumper, they are celebrating their 50th birthday.

The French – young and old – adore them. They eat 400 million of the bears each year. The seductive bears were invented by a confectioner from the north, Michel Cathy, who, the legend claims, bravely championed his recipe in the face of skepticism from superiors and has been vindicated by their triumph ever since.

Biting into an ourson guimauve, the French say, is like tasting Marcel Proust’s madeleine cake that launched his voyage into the remembrance of things past.

They come in milk or white chocolate, in cellophane packets from supermarkets, paper bags from small sweetshops or chic limited-edition designer tins.

Oursons guimauve have just been launched on the US market, a move that prompted some disgruntled voters to call for President Francois Hollande – long-nicknamed The Human Marshmallow (l’Homme de Guimauve) – to be dunked in chocolate and exported along with them.

The bears are predicted to make their French producers 900 million euros a year by 2015.

Cecilia Hermabessiere is in her sweetshop.

“I prefer oursons Lutti,” she says (Lutti is a sweet manufacturer).

“They’re almost the same, but larger. The marshmallow is firmer, creamy and slightly chewy. And they come coated in dark chocolate, which I always crave.”

She knows about sweets. Her little shop on the Rue Brea – busy with customers of all ages – has regional bonbons, chocolates and lollipops from all over the country. There are about 650 varieties of traditional sweets in France, the most for any one country in the world.

Cecilia Hermabessiere grew up with them. Her parents owned a patisserie – a cake shop and bakery – where sweets were always sold.

“Sales haven’t gone down,” she says.

“If anything, they’ve gone up. People need a treat and if there’s something they won’t do without, it’s chocolate or the comfort of their favorite childhood sweet or regional speciality from home.”

Shelves are lined with tall glass jars filled with glistening frou-frous bonbons (square-shaped boiled sweets), rondelles d’orange (slices of candied orange half-coated in bitter chocolate) and large cubes of rose and lemon Turkish delight heavy with powdered sugar.

Juicy, chocolate Muscat raisins, shining sugared almonds and caramelized hazelnuts, rows of amber barley sugar from Moret (a region in north-central France) and sticks of sucre de pomme (apple sugar from Rouen) bristle temptingly beside smooth peppermint lozenges from Lourdes made with holy water from the shrine and individually stamped with an image of the Virgin Mary.

Slabs of chocolate are sold by the kilo – milk or dark – with hazelnuts, almonds, crystallized ginger or filled with liquid caramel. There is a small hammer nearby to break off chunks.

“Children still eat a piece of bread and chocolate for their after-school gouter [teatime treat],” Cecilia Hermabessiere explains.

“It’s the original pain au chocolat – bread with chocolate – before the pastry version was ever thought of. There’s lots of nostalgia for childhood here in France, so grown-ups at the school gate often sneak a portion for themselves.”

Opposite a small park and playground shaded by large beech trees, Georges Marques has opened the sweetshop of his childhood dreams.

“We were Portuguese immigrants and didn’t have much money,” he says.

“[In 1970] for my eighth birthday, an uncle gave me a five franc piece. Sweets cost one centime each so that was a fortune. I went straight to my local patisserie and bought a huge bagful to share with my family. I burst in, crying out to my mother, <<When I grow up, I’m going to open the best sweetshop in the whole world>>.”

Georges Marques travels around France, personally tasting and selecting regional sweets. He hunts them down, then brings them to Paris and pops them in a jar in the window.

“People really appreciate it,” he says.

“They suddenly see a rare sweet from some tiny place that they love and rush in to eat it.”

Georges Marques has about 200 varieties, from those oursons guimauve to marshmallow Petit Jesus (small Jesus-shaped marshmallows) to such fancies as Les Tetines de la Reine Margot (Queen Margot’s Nipples) named after a beleaguered monarch notorious for her insatiable sexual appetites.

These are dome-shaped confections of milk chocolate, apricot, raisins soaked in Grand Marnier liqueur, all coated in white chocolate with a discreet, tasteful milk chocolate nipple.

An ever-popular gift, says Georges Marques, to cheer-up “les monsieurs”.

French marshmallow

• First made in France about 1850

• Called “pate de guimauve” or “guimauve” for short

• By late 19th Century, French manufacturers had started to use egg whites or gelatine combined with modified corn starch to create the chewy base

• It made the process of making marshmallow much less labor intensive

• The classic Bouquet d’Or Petit Ourson – chocolate-covered marshmallow bear – turned 50 this year

[youtube xp6cSz9_NYQ]