US medal-winning athletes at the Olympics will have to pay tax on their prize money – something which is proving controversial in the US.

But why are athletes from the US taxed when others are not?

The US, unlike most countries, has a “worldwide” system of tax, which means that money earned abroad is liable for US tax.

The US is right up there in the medals table, and has produced some of the finest displays in the Olympics so far.

Michael Phelps has broken the record for most Olympic medals ever, and 16-year-old rising star Gabby Douglas has won the all-round gold in the gymnastics – the first African-American woman to do so.

So the US is feeling pretty proud of its athletes right now. But not everyone is happy to hear that their Olympic medal-winning athletes are being taxed on their medal prize money.

Athletes are effectively being punished for their success, argues Florida Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican, who introduced a bill earlier this week that would eliminate tax on Olympic medals and prize money.

“Athletes representing our nation overseas in the Olympics shouldn’t have to worry about an extra tax bill waiting for them back home,” said Marco Rubio.

This, he said, is an example of the “madness” of the US tax system, which he called a “complicated and burdensome mess”.

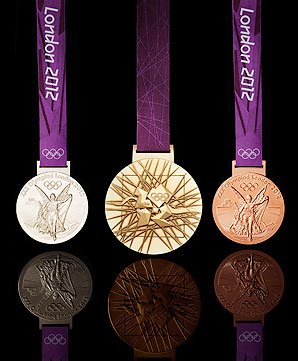

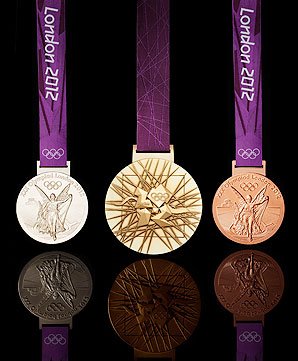

The US Olympic Committee awards prize money to its medal winners – $25,000 for gold, $15,000 for silver, and $10,000 for bronze.

This money is considered taxable income by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

According to the advocacy group Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), an athlete on the highest rate of tax (35%), could face a tax bill of $8,750.

The value of the medals themselves could be subject to tax too, according to the ATR – adding a further $236, $135 and $2 respectively for gold, silver and bronze.

The Olympic example highlights what they regard as the underlying problem of the US’ so-called “worldwide” tax model.

Under this system, earnings made by a US citizen abroad are liable for both local tax and US tax.

Most countries in the world have a “territorial” system of tax and apply that tax just once – in the country where it is earned.

With the Olympics taking place in London, the UK would, in theory, be entitled to claim tax on prize money paid to visiting athletes. But, as is standard practice for many international sporting events, it put in place a number of tax exemptions for competitors in the Olympics – including on any prize money.

That means that only athletes from countries with a worldwide tax system on individual income are liable for tax on their medals.

And there are only a handful of them in the world, says Daniel Mitchell, an expert on tax reform at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank – citing the Philippines and Eritrea as other examples.

But with tax codes so notoriously complicated, unravelling which countries would apply this in the context of Olympic prize money is a tricky task, he says.

Daniel Mitchell is a critic of the worldwide system, saying it effectively amounts to “double taxation” and leaves the US both at a competitive disadvantage, and as a bullyboy, on the world stage.

“We are the 800 lbs [360kg] gorilla in the world economy, and we can bully other nations into helping enforce our bad tax law.”

The tax burden may not be as heavy as it first appears, however, as there are a number of credits and tax treaties which can either exempt or reduce the amount due, says tax lawyer and blogger, Kelly Phillips Erb.

She believes that the US tax system needs to be modified, and – most importantly – simplified.

The Rubio bill – by adding another exemption to the already complicated tax code – would only make matters worse, she says.

Congress is about to go off on a one-month recess, and with the Olympics already well underway, this is, says Kelly Phillips Erb, more about “political grand-standing” than anything else.

Not all athletes get prize money along with an Olympic medal – it depends what country you come from.

Money is not awarded by the International Olympic Committee. The decision whether to offer prize money is made by the national Olympic Committees in each individual country, who also set the sum.

At the opposite end of the scale is Singapore, which is offering $800,000 (£515,000) for a gold medal.

Many countries in Central Asia are also offering large sums to medal winners.

John Hoberman, a sports historian and expert on doping at the University of Texas at Austin, says Americans are focusing on the wrong issue.

The real question, he believes, is whether athletes should be awarded prize money at all at the Olympics – and he is firmly in the “no” camp.

“Cash incentives are just an incentive to cheat,” says John Hoberman.

He believes the more money you offer, especially in poorer countries, the greater the chance an athlete will be tempted to dope.

How much for a gold medal at London 2012 Olympics:

• Singapore – $800,000

• Kazakhstan – $250,000

• Kyrgyzstan – $200,000

• Uzbekistan – $150,000

• Russia – $135,000

• Tajikistan – $63,000

• US – $25,000

• Australia – $20,000 plus face on a stamp

• UK – No money – but their face on a stamp