Proteus Biomedical, Redwood City, California, and the healthcare company Lloydspharmacy are about to launch digital pills in the United Kingdom, as they announced on January 13.

When a person is prescribed multiple drugs, that are required to be taken at various times, the compliance with physician’s advice becomes very difficult.

“Anyone taking several medications knows how easy it can be to lose track of whether or not you’ve taken the correct tablets that day. Add to that complex health issues and families caring for loved ones who many not live with them and you can appreciate the benefits of an information service that helps patients to get the most from their treatments and for families to help them to remain well,” said Steve Gray, healthcare services director of Lloydspharmacy.

According to World Health Organization around 50% of all patients do not take their medicines correctly. This can lead to people not getting the full benefits of treatment, or to harmful side-effects. NHS spends £400m a year on unused prescription medicines.

Digital pills or “intelligent medicines” help patients and their care-givers to keep track of which pills are taken at what time of day by chronically-ill patients, especially those with mental health problems.

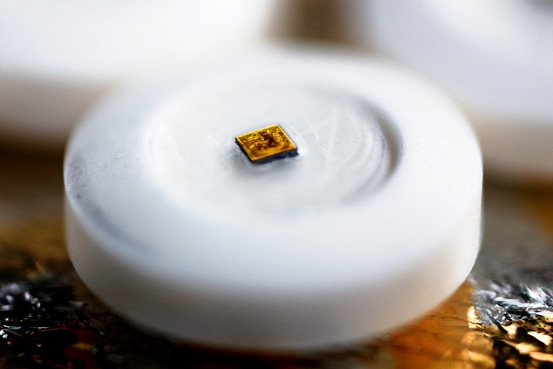

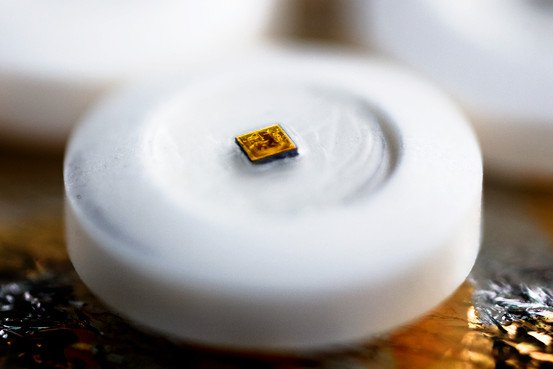

The “digital health product” (Helius) consists in “sensor-enabled tablets” designed to supervise patients’ medication use. The digestible sensor, smaller than a grain of sand, triggers the transmission of medical information from a patient’s body to the mobile phone of a relative or a care-giver.

“The most important and basic thing we can monitor is the actual physical use of the medicine. We have tested the system in hundreds of patients in many different therapeutic areas. It’s been tested in tuberculosis, in mental health, in heart failure, in hypertension and in diabetes,” said Andrew Thompson, chief executive of Proteus.

“In the future the goal is a fully integrated system that creates an information product that helps patients and their families with the demands of complex pharmacy. What we know is that we’ve created many pharmaceuticals with great potential but much of that potential is not realized because these drugs are not being used properly,” he said.

Sensors called “ingestible event markers” can be taken with medicines or during the production will be incorporated into pills. In this system, the sensors will be embedded in a placebo to be taken alongside a medicine. The edible microchip records the details of a patient’s pill regime.

How do the digital pills work?

The sensors are activated by stomach acid. They are powered like a “potato battery” (two different metals generate a current when inserted into the vegetable). Every sensor includes a very small quantity of copper and magnesium separated by a silicon membrane.

“If you swallow one of these devices, you are the potato that creates a voltage, and we use that to power the device that creates the signal,” said Thompson.

A device is attached to the skin (like a patch or a bandage) and is the only one that can detect the digital signal. The bandage must be worn for seven days, and includes a flexible battery and chip that records the information.

This device can monitor the patient’s response to medication by measuring temperature, heart and respiration rate. These findings can be transferred by Bluetooth wireless technology to a mobile phone and the patient can choose who can see these data.

Asides from these digital pills, other similar technologies were developed.

More than 30 years ago NASA produced ingestible thermometers to measure astronauts’ core temperatures. Some athletes are using these devices in recent times.

Camera pills are showing images of the inside of the digestive system for some years.

“There are a number of companies that have looked at putting technologies on pills for sensing inside the body,” said Jonathan Cooper, biomedical-engineering researcher, University of Glasgow, Scotland.

A problem appears when they try to make the digital pills more complicated.

“As you add sensor functionality you have greater power demands and have to make the pill larger,” Cooper said. As the pills enlarged they become harder to swallow and camera pills might sometimes be stuck in the digestive tract.

Internal monitoring technology also has to compete with sensor systems based outside the body. Cooper’s team tried to design digital pills for monitoring minute traces of blood in the lower colon, to screen for bowel cancer. In the end they found it easier to adapt their technology to analyze and monitor stool samples.

Lloydspharmacy intends to test if NHS patients would be prepared to pay privately for digital pills.

The pills will be marketed to people with chronic conditions, and it is possible that they will be available from September, probably at a starting cost of about £50 per week.