A new stem cell technique for growing working liver cells which could eventually avoid the need for liver transplant has been developed by British scientists from Sanger Institute and Cambridge University.

The British researchers used cutting-edge methods to correct a genetic mutation in stem cells derived from a patient’s skin biopsy, and then grew them into fresh liver cells. The scientists team put the new liver cells into and found they were fully functioning.

Dr. Allan Bradley, director of the Sanger Institute said:

“We have developed new systems to target genes and … correct … defects in patient cells.”

According to Dr. Allan Bradley, the Sanger Institute technique leaves behind no trace of the genetic manipulation, except for the gene correction.

“These are early steps, but if this technology can be taken into treatment, it will offer great possible benefits for patients,” Dr. Bradley added.

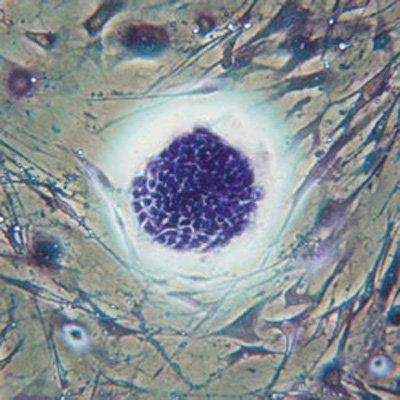

Stem cells are the body’s master cells, the source for all other cells, and specialists say they could transform medicine, providing treatments for blindness, spinal cord and other severe injuries, and new cells for damaged organs.

The Sanger Institute research is focused on two main forms:

1. embryonic stem cells, which are harvested from embryos,

2. reprogrammed cells, also known as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells), which are reprogrammed from ordinary skin or blood cells.

iPS cells were first discovered in 2006. The iPS cells seemed to be the perfect solution for the ethical debate over the use of embryonic stem cells, because they are made in a laboratory from ordinary skin or blood cells.

Embryonic stem cells are usually harvested from leftover embryos at fertility clinics and their use is opposed by many religious groups.

In recent years, some concerns have been raised that iPS cells may not be as “clean” or as capable as embryonic cells.

In 2010, a group led by Robert Lanza, of the U.S. firm Advanced Cell Technology, compared batches of iPS cells with embryonic stem cells and noticed the iPS cells died more quickly and were much less able to grow and expand.

The British study has been published in the journal Nature.

The research team took skin cells from a patient with a mutation in a gene called alpha1-antitrypsin, which is responsible for making a protein that protects against inflammation.

Patient with mutant alpha1-antitrypsin are not able to release the protein properly from the liver, so it becomes trapped there and eventually leads to liver cirrhosis and lung emphysema.

This is one of the most common inherited liver and lung disorders and affects about one in 2,000 people of North European origin, the researchers said.

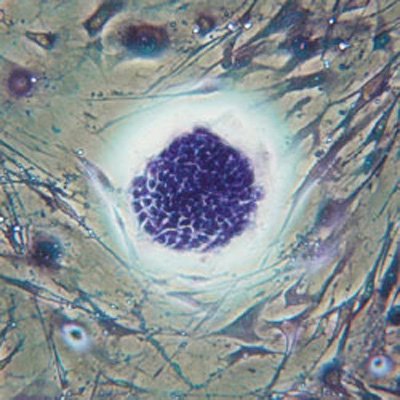

The scientists reprogrammed the skin cells back into stem cells before inserting a correct version of the gene using a DNA transporter called piggyBac.

The leftover piggyBac sequences were then removed from the cells, cleaning them up and allowing them to be converted into liver cells without any trace of residual DNA damage at the site of the genetic correction.

Professor David Lomas, from Cambridge University respiratory biology department said: “We then turned those cells into human liver cells and put them in a mouse and showed that they were viable.”

Dr. Ludovic Vallier, also from Cambridge University, said the results were a first step toward personalized cell therapy for genetic liver disorders.

“We still have major challenges to overcome…but we now have the tools necessary.”

The British researchers said it could be another 5 to 10 years before full clinical trials of the technique could be run using patients with liver disease.

If the new technique will succeed, liver transplants, which is a costly and complicated procedure, where patients need a lifetime of drugs to ensure the new organ is not rejected, could become a thing of the past.

Professor David Lomas said: “If we can use a patient’s own skins cells to produce liver cells that we can put back into the patient, we may prevent the future need for transplantation.”