An US federal advisory panel concluded that the PSA test should no longer be part of routine care in preventing prostate cancer.

According to Los Angeles Times, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s draft report, released yesterday, explained the reasons the common PSA (prostate-specific antigen) test should not be a routine one.

What was the panel trying to do?

The task force wasn’t trying to figure out whether screening for elevated levels of a protein called prostate-specific antigen (PSA) would save any lives at all; the answer to that is clearly yes.

Rather, the question before the 16-member panel was whether widespread PSA testing saves enough lives to justify the considerable medical fallout — including loss of urinary control and impotence — to men whose lives are not saved by the test.

They said the answer was no: “The vast majority of men who are treated do not have prostate cancer death prevented or lives extended from that treatment, but are subjected to significant harms.”

Dr. Michael LeFevre, a family medicine doctor at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and co-vice chairman of the task force, said in an interview Friday that he understood why many people gave the report a chilly reception.

“Any time a medical test or treatment that we believe should work is subjected to science and the science doesn’t show what we hoped for, it’s very disturbing to the medical establishment and to patients,” he said.

“We have to eat a pretty big chunk of crow and say this didn’t turn out to be true.”

Dr. J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who wasn’t involved in the task force review, said the panel’s conclusions were reasonable. “We have a culture of patients and families and physicians and others who believe strongly that the PSA test works, when the reality is the evidence is suggesting that is just not the case,” he said.

How is the PSA test used?

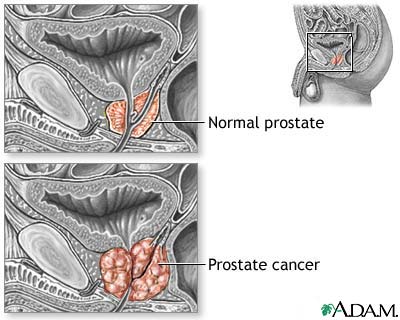

Prostate tumors may cause the prostate gland to ramp up production of prostate specific antigen, an ingredient needed to make semen. If that happens, the amount of PSA that gets into the bloodstream will rise above its usual trickle, and the test attempts to measure that.

The FDA approved the PSA test as a screening exam for men 50 and older in 1994 after two studies credited the test with finding more cancers than digital rectal exams and ultrasounds alone.

Doctors may suspect tumor growth in men with PSA levels above 4 nanograms per milliliter of blood or whose levels rise by more than 0.35 ng/mL in a year.

But PSA level alone isn’t proof of cancer — other problems, such as inflammation or benign prostatic hyperplasia, can also send more protein into the blood. The only sure way to confirm a cancer is to remove cells from the prostate and examine them under a microscope. If there is a malignancy, treatment can include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and hormone therapy.

So what’s the problem?

The test is not very good at separating men with prostate cancer from men without it. About two-thirds of men who have a PSA reading above 4 ng/mL do not have the disease, according to the American Cancer Society. Meanwhile, nearly one-third of men with PSA levels in the safe range have been found to harbor cancer cells in their prostates.

Autopsy studies have found prostate cancer in one-third of men between 40 and 60, and in 75% of men over 85; in most of those cases, the cancers are harmless.

“Many men with localized prostate cancer will never have problems,” said Dr. Roger Chou of Oregon Health & Science University, part of a group that reviewed evidence for the panel. “That’s a really hard concept for people, but it’s been known for a long time.”

The biggest knock on the test is that despite finding more cancers, it doesn’t actually lead to a reduction in deaths — the ultimate goal of any cancer screening program.

When a PSA test turns up prostate cancer in a man with no outward symptoms, that early warning could help him beat a tumor that otherwise would have killed him. But there are two other possibilities: Either the tumor is so aggressive that the patient dies anyway, or — as is usually the case — it is so slow-growing that it wouldn’t have been fatal, even if left untreated.

The overwhelming majority of cancers fall into the last group, the task force wrote: Fully 95% of men whose prostate cancers are detected with PSA tests will be alive 12 years later even if they don’t get treatment. And, the panel added, no study on prostate cancer screening has ever shown that screening reduces the number of deaths.

Even if the test isn’t perfect, how can it hurt?

Just because the test isn’t helpful doesn’t mean that it’s harmless. The task force noted that men whose PSA scores are suspect but who don’t have cancer can needlessly worry about the disease and undergo biopsies that can cause fever, infections, bleeding, pain and temporary problems with urination.

When patients have their prostates removed — often to treat cancers that never would have harmed them — up to 0.5% die within a month due to complications from surgery and an additional 1% to 7% have serious problems but survive.

Between 20% and 30% of men who have surgery and radiation wind up with erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence and other adverse effects, studies have shown. And about 40% of men who take pills to suppress hormones that can feed prostate cancer cells develop erectile dysfunction and other problems, the task force wrote.

As more men are screened, more are subjected to the harms of biopsies and treatment for a disease that wasn’t likely to kill them in the first place, the task force concluded. Between 1985 and 2005, an estimated 1 million American men have had surgery or radiation for prostate cancer as a result of PSA testing.

How firm is the evidence?

The panel based its conclusions mainly on five large randomized clinical trials, including two published in 2009 that had data from nearly 240,000 men. The panel said the strength of the evidence against widespread PSA testing was “at least fair.”

The task force recognized that many men and their doctors would want to continue using the screening test out of habit or for other reasons. But men should not opt for the test unless they understand both the benefits and the costs, they wrote.

More research is needed to help doctors figure out which men with elevated PSA levels are harboring aggressive tumors that can respond to treatment and which men would be best left alone, the task force wrote. It would also be helpful to know whether men with prostate cancer can be safely monitored with “watchful waiting” and postpone surgery and other treatments until their disease worsens, if it does, the panel added. Two large clinical trials are studying this question now.

What happens next?

A four-week public comment period on the draft recommendation will begin October 11. After that, the task force will work on a final draft. There is no estimate for how long that might take.