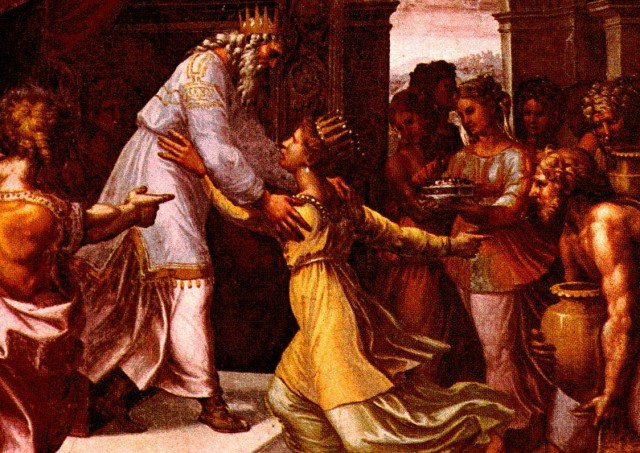

Scientists claim they found that clues to the origins of the Queen of Sheba legend are written in the DNA of some Africans.

Genetic research suggests Ethiopians mixed with Egyptian, Israeli or Syrian populations about 3,000 years ago.

This is the time the queen, mentioned in great religious works, is said to have ruled the kingdom of Sheba.

The research, published in The American Journal of Human Genetics, also sheds light on human migration out of Africa 60,000 years ago.

According to fossil evidence, human history goes back longer in Ethiopia than anywhere else in the world. But little has been known until now about the human genetics of Ethiopians.

Professor Chris Tyler-Smith of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK, a researcher on the study, said: “Genetics can tell us about historical events.

“By analyzing the genetics of Ethiopia and several other regions we can see that there was gene flow into Ethiopia, probably from the Levant, around 3,000 years ago, and this fits perfectly with the story of the Queen of Sheba.”

Lead researcher Luca Pagani of the University of Cambridge and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute added: “The genetic evidence is in support of the legend of the Queen of Sheba.”

More than 200 individuals from 10 Ethiopian and two neighboring African populations were analyzed in the largest genetic investigation of its kind on Ethiopian populations.

About a million genetic letters in each genome were studied. Previous Ethiopian genetic studies have focused on smaller sections of the human genome and mitochondrial DNA, which passes along the maternal line.

Dr. Sarah Tishcoff of the Department of Genetics and Biology at the University of Pennsylvania, said Ethiopia would be an important region to study in the future.

Commenting on the study, she said: “Ethiopia is a very diverse region culturally and linguistically but, until now, we’ve known little about genetic diversity in the region.

“This paper sheds light on the very interesting recent and ancient population history of a region that played an important role in both recent and ancient human migration events.

“In particular, the inference of timing and location of admixture with populations from the Levant is very interesting and is a unique example of how genetic data can be integrated with historical data.”

The scientists acknowledge that there are uncertainties about dating, with a probable margin of error of a few hundred years either side of 3,000 years.

They plan to look at all three billion genetic letters of DNA in the genome of individual Ethiopians to learn more about human genetic diversity and evolution.