Home Tags Posts tagged with "plos one"

plos one

British researchers have made a device that can “smell” bladder cancer in urine samples.

The device uses a sensor to detect gaseous chemicals that are given off if cancer cells are present.

Early trials show the tests gives accurate results more than nine times in 10, its inventors told PLoS One journal.

However, experts say more studies are needed to perfect the test before it can become widely available.

British researchers have made a device that can “smell” bladder cancer in urine samples

Doctors have been searching for ways to spot this cancer at an earlier stage when it is more treatable.

And many have been interested in odors in urine, since past work suggests dogs can be trained to recognize the scent of cancer.

Prof. Chris Probert, from Liverpool University, and Prof. Norman Ratcliffe, of the University of the West of England, say their new device can read cancer smells.

“It reads the gases that chemicals in the urine can give off when the sample is heated,” said Prof. Norman Ratcliffe.

To test their device, they used 98 samples of urine – 24 from men known to have bladder cancer and 74 from men with bladder-related problems but no cancer.

Prof. Chris Probert said the results were very encouraging but added: “We now need to look at larger samples of patients to test the device further before it can be used in hospitals.”

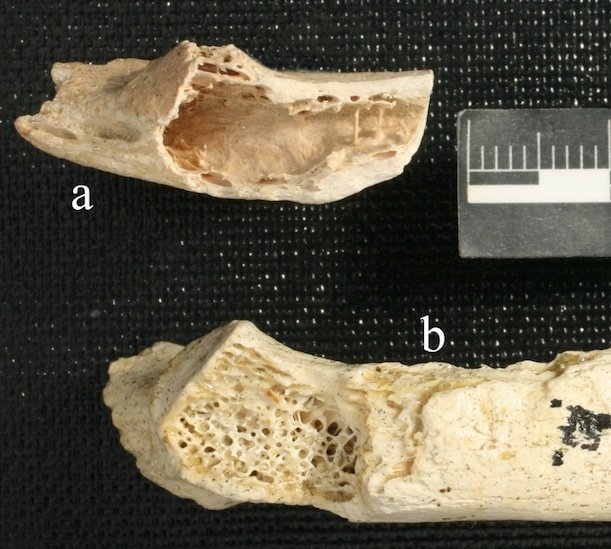

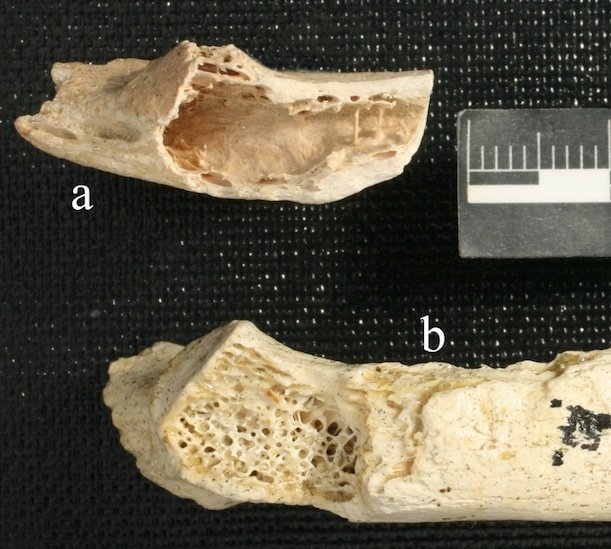

According to a fossil study, a Neanderthal living 120,000 years ago had a cancer that is common today.

A fossilized Neanderthal rib found in a shallow cave at Krapina, Croatia, shows signs of a bone tumor.

The discovery is the oldest evidence yet of a tumor in the human fossil record, say US scientists.

The research, published in the journal PLOS One, gives clues to the complex history of cancer in humans.

A fossilized Neanderthal rib found in a shallow cave at Krapina, Croatia, shows signs of a bone tumor

Until now, the earliest known bone cancers have been identified in ancient Egyptian remains from about 1,000-4,000 years ago.

“It’s the oldest tumor found in the human fossil record,” said Dr. David Frayer, the University of Kansas anthropologist who led the US team.

“It shows that living in a relatively unpolluted environment doesn’t necessarily protect you against cancer, even if you were a Neanderthal living 120,000 years ago.”

The fossil was uncovered from an important archaeological site that has yielded almost 900 ancient human bones, along with stone tools.

The cancerous rib is an incomplete specimen, so the overall health impact of the tumor on the individual cannot be established.

The tumor was diagnosed by a medical radiologist from X-rays and CT scans.

Although efforts to extract ancient DNA from the Neanderthal fossil have proved unsuccessful, the researchers hope other fossils may shed light on cancer in prehistoric humans.

A study in the journal PLoS ONE suggests that some people responding to treatments that have no active ingredients in them may be down to their genes.

The so-called “placebo effect” was examined in 104 patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in the US.

Those with a particular version of the COMT gene saw an improvement in their health after placebo acupuncture.

The scientists warn that while they hope their findings will be seen in other conditions, more work is needed.

Edzard Ernst, a professor of complementary medicine at the University of Exeter, said: “This is a fascinating but very preliminary result.

“It could solve the age-old question of why some individuals respond to placebo, while others do not.

“And if so, it could impact importantly on clinical practice.

“But we should be cautious – the study was small, we need independent replications, and we need to know whether the phenomenon applies just to IBS or to all diseases.”

The placebo effect is when a patient experiences an improvement in their condition while undergoing an inert treatment such as taking a sugar pill or, in this case, placebo acupuncture, where the patient believes they are receiving acupuncture but a sham device prevents the needles going into their body.

Two groups in the study had this type of treatment. One group received it in a business-like clinical manner and the other from a warm supportive practitioner. A third randomly chosen group received no treatment at all.

After three weeks the patients were asked if they had seen an improvement in their IBS, a common gastrointestinal disease that can cause abdominal pain and discomfort.

The team then used blood samples to look at what variant the individual had of the catechol-O-methyltranferase (COMT) gene. This plays a role in the dopamine pathway, a chemical known to produce a feel-good state.

Paper author Dr. Kathryn Hall, from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), said this gene had been chosen because “there has been increasing evidence that the neurotransmitter dopamine is activated when people anticipate and respond to placebos”.

The researchers found individuals with a COMT variant that triples the amount of dopamine in the front of the brain felt no improvement without treatment but an improvement with the placebo acupuncture.

Ted Kaptchuk, director of the Program in Placebo Studies and Therapeutic Encounter at BIDMC, said: “We wanted to tease apart the different doses of placebo.

“We got an effect in individuals with this specific genetic signature for the general placebo, but an even bigger effect in the elaborate placebo where warmer care was given.

“You can really see the advantage of a positive doctor-patient relationship.”

Fabrizio Benedetti, professor of neurophysiology at the University of Turin Medical School, Italy, warned that dopamine may not be the only chemical involved with the placebo effect.

“A previous study on the genetics of placebo in social anxiety disorder showed that it is serotonin that is associated to placebo responsiveness and not dopamine,” he said.

“While this is a very interesting work, what we have learned in the past few years is that there is not a single placebo response and a single mechanism, but many, across different medical conditions and therapeutic interventions.”

Mice may have the ability to learn songs based on the sounds they hear, according to US researchers.

They found that when male mice were housed together they learned to match the pitch of their songs to each other.

Mice also share some behavioral and brain mechanisms involved in vocal learning with songbirds and humans, say the researchers.

But some scientists are skeptical, saying the evidence doesn’t support the claim.

Details of the study are published in the Journal Plos One.

Previous research in this field has shown that male mice can sing complex songs when exposed to females and these play an important part in courtship.

These murine serenades are ultrasonic. At between 50 and 100KHz, they are far above the hearing range of humans. When processed to make them audible to humans, they sound like a series of plaintive whistles.

It has long been assumed that mice were incapable of modifying the sequence or the pitch of these sounds. This ability, called vocal learning, is rare in the natural world. It is restricted to some birds such as parrots and song birds along with whales, dolphins, sea lions, bats and elephants.

But in these experiments, researchers from Duke University in North Carolina say they found that mice have both the brain circuits and the behavioral attributes consistent with vocal learning.

Dr. Erich Jarvis, who oversaw the study, said it had changed his understanding of the way mice make sound.

“In mice we find that the pathways that are at least modulating these vocalizations are in the forebrain, in places where you actually find them in humans,” he said.

He says the study does not have clear evidence that mice have the very same vocal abilities as birds and humans. He believes there is a spectrum where different species have vocal skills to different degrees.

“We think mice are intermediate in this ability between a chicken and a song bird or even a non human primate and a human,” Dr. Erich Jarvis said.

When male mice with different vocal pitches were housed together, the team found that the pitch of their songs gradually converged over a period of eight weeks.

Dr. Erich Jarvis argues that this is an important development: “When we put a female in the cage with two males, we then found that one male would change his pitch to match the other. It was usually the smaller animal changing the pitch to match the larger animal.”

But others are less certain. Dr. Kurt Hammerschmidt, an expert in vocal communication at the German Primate Centre in Goettingen, cast doubt on the study’s claim about the vocal behavior of male mice.

“The pitch convergence story is less convincing,” he says.

But Erich Jarvis refutes this, saying the skepticism is unfounded.

“His complaint was that we don’t have enough animals, but we found this in 12 mouse pairs and in every single pair… at least in our eyes it’s quite reliable and statistically significant,” he said.

Scientists have devised a formula that predicts a woman’s chances of pregnancy.

The formula combines information about how fertility drops with age with the length of time a woman has been trying to start a family, to come up with their odds of conceiving.

For example, they have worked out that the average 25-year-old who has been trying to get pregnant for six months has a 15% chance of doing so in the following month.

By the age of 30, her odds are 13% and, at 35, they have dropped below 10%.

The speeding up of the biological clock mean the chances of pregnancy plummet after 35.

The average 40-year-old who has been trying for six months has just a 5% of getting pregnant in the next month – or odds of one in 20.

Scientists have devised a formula that predicts a woman’s chances of pregnancy

The calculations also show that when a woman is 25, it will take 13 months for her odds of conceiving quickly to fall below 10%.

But a 35-year-old woman has just six months before her chances are so slim.

The long-standing rule of thumb is that those trying for a family should wait a year before seeking help, although doctors are increasingly acknowledging the impact of age.

The researchers, from the University of Warwick and the London School of Economics in UK, say that more detailed information could make it easier for couples to discuss fertility issues with their GP.

Professor Geraldine Hartshorne said: “People feel embarrassed and upset and don’t want to go to the doctor. Men, in particular, can be a little bit reluctant.

“As time goes by and people have been trying for a while, they start to get stressed and upset and that can affect their chances of having sex and then becoming pregnant. Approaching a doctor about a personal matter is daunting, so knowing the right time to start investigations would be a useful step forward.”

Writing in the journal PLoS One, Prof. Geraldine Hartshorne also warns that taking too long to conceive could indicate that the resulting pregnancy might be risky.

The work could help doctors to decide whether to refer patients for costly and uncomfortable tests or advise them to keep trying for a baby a little longer.

The researchers have passed their work to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, which formulates health guidelines. In future, it may be possible to create an online calculator that provides couples with a personalized prediction.

Prof. Geraldine Hartshorne added that factors such as smoking or being fat are “not the most important things” when it comes to conceiving. However, a healthy lifestyle will boost the odds of a healthy baby.

She said: “If your tubes are blocked, giving up smoking really isn’t going to make a difference, but things like smoking and obesity do have important effects when you do get pregnant and in that respect they should be addressed as soon as possible.”

British researchers at the University of Bristol believe the shape of beer glasses affects the speed people drink.

Their study, published in the journal PLoS ONE, suggests people drink more quickly out of curved glasses than straight ones.

They argue that the curvy glassware makes pacing yourself a much greater challenge.

A group of 159 men and women were filmed drinking either soft drinks or beer as part of the study. The glasses all contained around half a pint of liquid, but some of the glasses were straight while others were very curved.

There was no difference in the drinking time for soft drinks. People drinking from both straight and curved glasses finished after around seven minutes.

British researchers at the University of Bristol believe the shape of beer glasses affects the speed people drink

However, for the beer drinkers there was a large difference between the two groups. While it took around seven minutes for people drinking from a curved glass to polish off their half pint, it took 11 minutes for those drinking from a straight glass.

The report said: “Drinking time is slowed by almost 60% when an alcoholic beverage is presented in a straight glass compared with a curved glass.”

The researchers thought that curvy glasses made it harder to pace drinking because judging how much was in the glass became more difficult owing to its curved shape.

The group of drinkers was shown a variety of pictures of partially-filled beer glasses and asked to say whether they were more or less than half full.

The team said people were more likely to get the answer wrong when assessing the amount of liquid in curved glasses.

The lead researcher Dr. Angela Attwood said: “They are unable to judge how quickly they are drinking so cannot pace themselves.”

She suggested that people were not concerned about pacing themselves with soft drinks, which could explain why glass shape had no effect on them.

However, the study looked only at the time taken to finish one drink in a laboratory setting. So it is not certain what happens on an evening out if multiple drinks are consumed.

She said altering the glasses used in pubs could “nudge” people to drink more healthily by “giving control back”.

The shape of a glass has already been shown to affect how much alcohol people pour. A study in 2005 showed people were more likely to pour extra alcohol into short, wide glasses than tall, narrow ones.

A team of doctors claim that “super-fertility” may explain why some women have multiple miscarriages.

They say the wombs of some women are too good at letting embryos implant, even those of poor quality which should be rejected.

The UK-Dutch study published in the journal PLoS ONE said the resulting pregnancies would then fail.

One expert welcomed the findings and hoped a test could be developed for identifying the condition in women.

A team of doctors claim that "super-fertility" may explain why some women have multiple miscarriages

Recurrent miscarriages – losing three or more pregnancies in a row – affect one in 100 women in the UK.

Doctors at Princess Anne Hospital in Southampton and the University Medical Center Utrecht, took samples from the wombs of six women who had normal fertility and six who had had recurrent miscarriages.

High or low-quality embryos were placed in a channel created between two strips of the womb cells.

Cells from women with normal fertility started to grow and reach out towards the high-quality embryos. Poor-quality embryos were ignored.

However, the cells of women who had recurrent miscarriages started to grow towards both kinds of embryo.

Prof. Nick Macklon, a consultant at the Princess Anne Hospital, said: “Many affected women feel guilty that they are simply rejecting their pregnancy.

“But we have discovered it may not be because they cannot carry, [but] it is because they may simply be super-fertile, as they allow embryos which would normally not survive to implant.”

He added: “When poorer embryos are allowed to implant, they may last long enough in cases of recurrent miscarriage to give a positive pregnancy test.”

This theory still needs further testing and will not explain all miscarriages.

New research has shown that when placed under stressful situations, men rate larger women as more attractive.

British researchers found that men exposed to tasks that were designed to put them under pressure preferred a wider range of female body sizes.

They conclude that stress can act to alter judgments of potential partners.

The work by a team from London and Newcastle is published in the open access journal Plos One.

“There’s a lot of literature suggesting that our BMI (body mass index) preferences are hard-wired, but that’s probably not true,” said co-author Dr. Martin Tovee, from Newcastle University.

New research has shown that when placed under stressful situations, men rate larger women as more attractive

Dr. Martin Tovee and his colleague, Dr. Viren Swami, have previously researched what factors could alter BMI preferences, including publishing a paper in the British Journal of Psychology on the effect of hunger, and the influence of the media.

But through this new work they aimed to investigate whether known cross-cultural differences in body size preferences linked to stress were also mirrored in short-term stressful situations.

“If you look at environments where food is scarce, people’s preferences for body size in a potential partner are shifted. [The preference] appears to be much heavier compared to environments where there’s plenty of food and a much more relaxed atmosphere,” he explained.

“If you’re living a far more stressful, subsistence lifestyle, you’re going to have higher stress levels.”

To simulate heightened stress, a test group of men were placed in interview and public speaking scenarios and their BMI preferences compared against a control group of non-stressed men.

The results indicated that the change in “environmental conditions” led to a shift of weight preference towards heavier women with the men considering a wider range of body sizes attractive.

“These changes are comparatively minor in comparison to those you get between different [cross-cultural] environments. But they suggest certain factors which might combine with others and cause this shift,” Dr. Martin Tovee said.

The research supports other work that has shown perceptions of physical attractiveness alter with levels of economic and physiological stress linked to lifestyle.

“If you follow people moving from low-resource areas to higher resource-areas, you find their preferences shift over the course of about 18 months. In evolutionary psychology terms, you try to fit your preferences to what works best in a particular environment,” said Dr. Martin Tovee.

Moreover, the researchers were keen to emphasize how fluctuating environmental conditions could alter the popular perception of an “ideal” body size.

“There’s a continual pushing down of the ideal, but this preference is flexible. Changing the media, changing your lifestyle, all these things can change what you think is the ideal body size,” he said.

A new research has contradicted the idea that exercise is more important than diet in the fight against obesity.

A study of the Hadza tribe, who still exist as hunter gatherers, suggests the amount of calories we need is a fixed human characteristic.

This suggests Westerners are growing obese through over-eating rather than having inactive lifestyles, say scientists.

One in 10 people will be obese by 2015.

And, nearly one in three of the worldwide population is expected to be overweight, according to figures from the World Health Organization.

The Western lifestyle is thought to be largely to blame for the obesity “epidemic”.

Various factors are involved, including processed foods high in sugar and fat, large portion sizes, and a sedentary lifestyle where cars and machines do most of the daily physical work.

A study of the Hadza tribe, who still exist as hunter gatherers, suggests the amount of calories we need is a fixed human characteristic

The relative balance of overeating to lack of exercise is a matter of debate, however.

Some experts have proposed that our need for calories has dropped drastically since the industrial revolution, and this is a bigger risk factor for obesity than changes in diet.

The study, published in the PLoS ONE journal, tested the theory, by looking at energy expenditure in the Hadza tribe of Tanzania.

The Hadza people, who still live as hunter gatherers, were used as a model of the ancient human lifestyle.

Members of the 1,000-strong population hunt animals and forage for berries, roots and fruit on foot, using bows, small axes, and digging sticks. They don’t use modern tools or guns.

A team of scientists from the US, Tanzania and the UK, measured energy expenditure in 30 Hadza men and women aged between 18 and 75.

They found physical activity levels were much higher in the Hadza men and women, but when corrected for size and weight, their metabolic rate was no different to that of Westerners.

Dr. Herman Pontzer of the department of anthropology at Hunter College, New York, said everyone had assumed that hunter gatherers would burn hundreds more calories a day than adults in the US and Europe.

The data came as a surprise, he said, highlighting the complexity of energy expenditure.

But he stressed that physical exercise is nonetheless important for maintaining good health.

“This to me says that the big reason that Westerners are getting fat is because we eat too much – it’s not because we exercise too little,” said Dr. Herman Pontzer.

“Being active is really important to your health but it won’t keep you thin – we need to eat less to do that.

“Daily energy expenditure might be an evolved trait that has been shaped by evolution and is common among all people and not some simple reflection of our diverse lifestyles.”

Supervolcanoes were thought to exist for as much as 200,000 years before releasing their vast underground pools of molten rock

Supervolcanoes, the largest volcanoes on Earth, may take as little as a few hundred years to form and erupt.

Supervolcanoes were thought to exist for as much as 200,000 years before releasing their vast underground pools of molten rock.

Researchers reporting in Plos One have sampled the rock at the supervolcano site of Long Valley in California.

Their findings suggest that the magma pool beneath it erupted within as little as hundreds of years of forming.

That eruption is estimated to have happened about 760,000 years ago, and would have covered half of North America in its ash.

Such super-eruptions can release thousands of cubic kilometres of debris – hundreds of times larger than any eruption seen in the history of humanity.

Eruptions on this scale could release enough ash to influence the global weather for years, and one theory holds that the Lake Toba eruption in Indonesia about 70,000 years ago had long-term effects that nearly wiped out humans altogether.

What little is known about the formation of these supervolcanoes is largely based on the study of crystals of a material called zircon, which contains small amounts of radioactive elements whose age can be estimated using the same techniques used to date archaeological artefacts and dinosaur bones.

Zircon studies to date have suggested that the time between the formation of the enormous magma pools and the eventual super-eruptions can be measured in the hundreds of thousands of years.

Now, Guilherme Gualda of Vanderbilt University and his colleagues present several lines of evidence from the Bishop Tuff deposit at Long Valley, suggesting that the pools are “ephemeral” – lasting as little as 500 years before eruption.

Initially, the magma pools are nearly purely liquid rock, with few bubbles or re-crystallized minerals.

Over time, crystals develop, but the process stops at the point of the eruption. As a result, the characteristic development time of these crystals can also give an estimate of how long a magma pool existed before erupting.

Rather than zircon, the team’s target was crystals of the common mineral quartz.

Because the processes and timescales of quartz formation in the extraordinary underground conditions of a magma pool are well-known, the team was able to determine how long the crystals were forming within Long Valley’s supervolcano before being spewed out in the eruption.

Their estimates suggest the quartz formed over a range of time between 500 and 3,000 years.

“Our study suggests that when these exceptionally large magma pools form they are ephemeral and cannot exist very long without erupting,” said Dr. Guilherme Gualda.

“The fact that the process of magma body formation occurs in historical time, instead of geological time, completely changes the nature of the problem.”

At present, geologists do not believe that any of Earth’s known giant magma pools are in imminent danger of eruption, but the results suggest future work to better understand how the pools develop, and aim ultimately to predict devastating super-eruptions.

Scientists have discovered that nearly twice as many emperor penguins inhabit Antarctica as was previously thought.

UK, US and Australian scientists used satellite technology to trace and count the iconic birds, finding them to number almost 600,000.

Their census technique relies in the first instance on locating individual colonies, which is done by looking for big brown patches of guano (penguin poo) on the white ice.

High resolution imagery is then used to work out the number of birds present.

It is expected that the satellite mapping approach will provide the means to monitor the long-term health of the emperor population.

Climate modeling has suggested their numbers could fall in the decades ahead if warming around Antarctica erodes the sea ice on which the animals nest and launch their forays for seafood.

“If we want to understand whether emperor penguins are endangered by climate change, we have to know first how many birds there are currently and have a methodology to monitor them year on year,” said Peter Fretwell from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

“This study gives us that baseline population, which is quite surprising because it’s twice as many as we thought, but it also gives us the ability to follow their progress to see if that population is changing over time,” he said.

Scientists have discovered that nearly twice as many emperor penguins inhabit Antarctica as was previously thought

The scientists have reported their work in the journal PLoS One.

Their survey identified 44 key penguin colonies on the White Continent, including seven that had not previously been recognized.

Although finding a great splurge of penguin poo on the ice is a fairly straightforward – if laborious – process, counting individual birds in a group huddle is not, even in the highest resolution satellite pictures.

This means the team therefore had to calibrate their analysis of the colonies by using ground counts and aerial ph

Peter Fretwell and colleagues totted 595,000 penguins, which is almost double the previous estimates of 270,000-350,000 emperors. The count is thought to be the first comprehensive census of a species taken from space.

Co-author Michelle LaRue from the University of Minnesota said the monitoring method provided “an enormous step forward in Antarctic ecology”.

“We can conduct research safely and efficiently with little environmental impact,” she explained.

“The implications for this study are far-reaching. We now have a cost-effective way to apply our methods to other poorly understood species in the Antarctic.”

The extent of sea ice in the Antarctic has been relatively stable in recent years (unlike in the Arctic), although this picture hides some fairly large regional variations.

Nonetheless, computer modeling suggests a warming of the climate around Antarctica could result in the loss of more northern ice floes later this century.

If that happens, it might present problems for some emperor colonies if the seasonal ice starts to break up before fledglings have had a chance to acquire their full adult, waterproof plumage.

And given that the krill (tiny crustaceans) that penguins feed on are also dependent on the ice for their own existence (they feed on algae on the ice) – some colonies affected by eroded floes could face a double-whammy of high fledgling mortality and restricted food resources. But this can all now be tested by the methodology outlined in the PLoS paper.

“The emperor penguin has evolved into a very narrow ecological niche; it’s an animal that breeds in the coldest environment in the world,” explained Peter Fretwell.

“It currently has an advantage in that environment because there are no predators and no competition for its food.

“If Antarctica warms so that predators and competitors can move in, then their ecological niche no longer exists; and that spells bad news for the emperor penguin.”

US researchers have found that the obesity problem may be much worse than previously thought.

Experts said using the Body Mass Index (BMI) to determine obesity was underestimating the issue.

The US study, published in the journal PLoS One, said up to 39% of people who were not currently classified as obese actually were.

The authors said “we may be much further behind than we thought” in tackling obesity.

BMI is a simple calculation which combines a person’s height and weight to give a score which can be used to diagnose obesity. Somebody with a BMI of 30 or more is classed as obese.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control, at least one in three Americans are obese.

Other ways of diagnosing obesity include looking at how much of the body is made up of fat. A fat percentage of 25% or more for men or 30% or more for women is the threshold for obesity.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control, at least one in three Americans are obese

One of the researchers Dr. Eric Braverman said: “The Body Mass Index is an insensitive measure of obesity, prone to under-diagnosis, while direct fat measurements are superior because they show distribution of body fat.”

The team at the New York University School of Medicine and the Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, looked at records from 1,393 people who had both their BMI and body fat scores measured.

Their data showed that most of the time the two measures came to the same conclusion. However, they said 539 people in the study – or 39% – were not labeled obese according to BMI, but their fat percentage suggested they were.

They said the disparity was greatest in women and became worse when looking at older groups of women.

“Greater loss of muscle mass in women with age exacerbates the misclassification of BMI,” they said.

They propose changing the thresholds for obesity: “A more appropriate cut-point for obesity with BMI is 24 for females and 28 for males.”

A BMI of 24 is currently classed as a “normal” weight.

“By our cut-offs, 64.1% or about 99.8 million American women are obese,” they said.

It is not the first time BMI has been questioned. A study by the University of Leicester said BMIs needed to be adjusted according to ethnicity.