The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – the world’s biggest ever trade deal – was signed into existence on October 5.

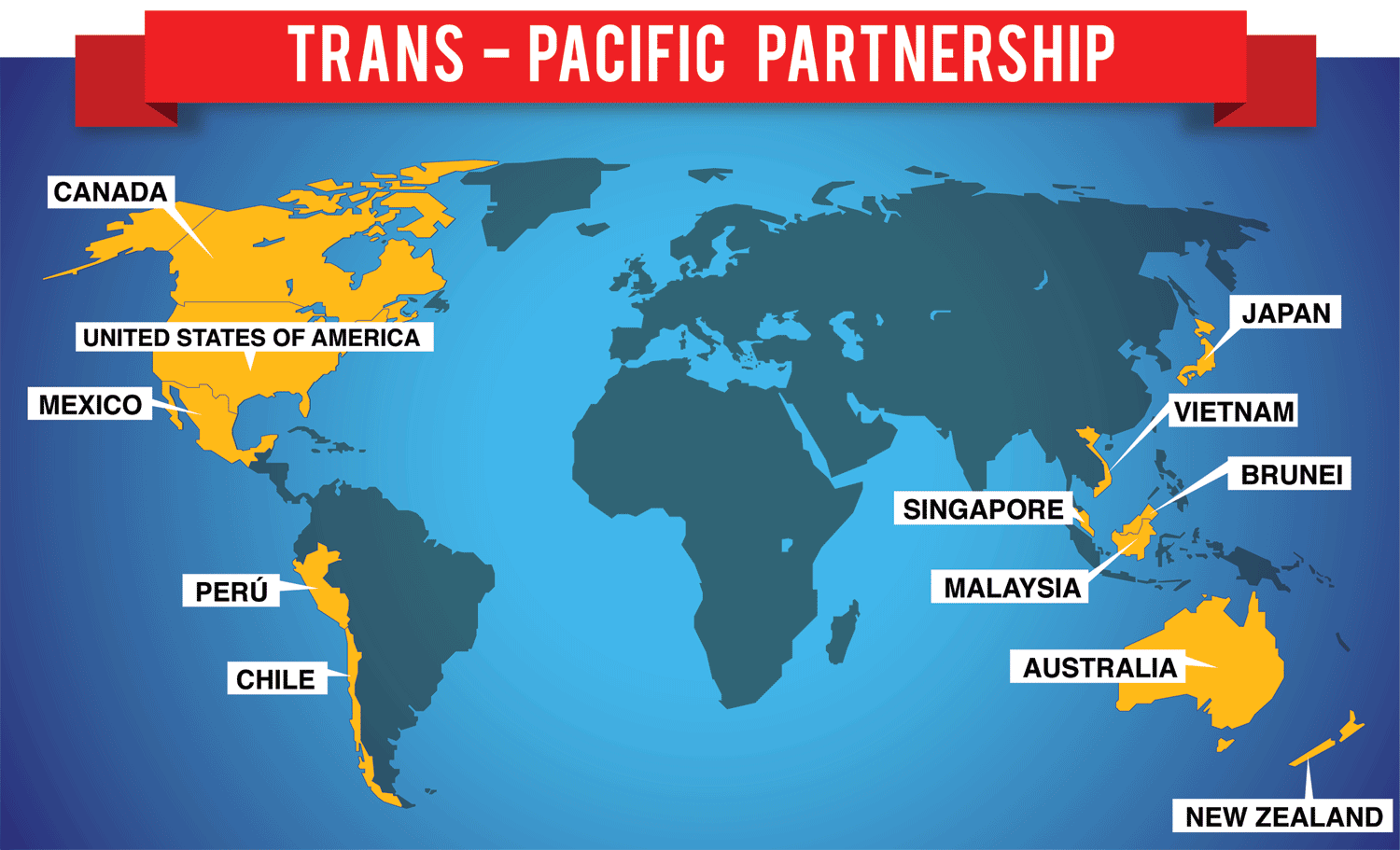

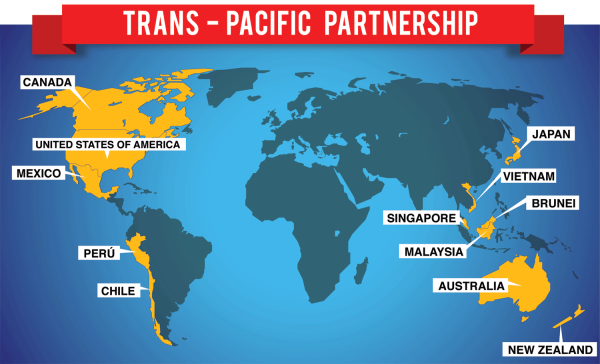

The TPP cuts trade tariffs and sets common standards in trade for 12 Pacific rim countries, including the United States and Japan.

It marks the end of five years of often bitter and tense negotiations.

The deal covers about 40% of the world economy and was signed after five days of talks in Atlanta in the US.

Supporters say it could be worth billions of dollars to the countries involved but critics say it was negotiated in secret and is biased towards corporations.

Despite the success of the negotiations, the deal still has to be ratified by lawmakers in each country.

For President Barack Obama, the trade deal is a major victory.

He said: “This partnership levels the playing field for our farmers, ranchers, and manufacturers by eliminating more than 18,000 taxes that various countries put on our products.”

Senator Bernie Sanders, a Democratic presidential candidate, said: “Wall Street and other big corporations have won again.”

Bernie Sanders said the deal would cost US jobs and hurt consumers and that he would “do all that I can to defeat this agreement” in Congress.

China was not involved in the agreement, and the Obama administration is hoping it will be forced to accept most of the standards laid down by TTP.

He said: “When more than 95% of our potential customers live outside our borders, we can’t let countries like China write the rules of the global economy.

“We should write those rules, opening new markets to American products while setting high standards for protecting workers and preserving our environment.”

Japan’s PM Shinzo Abe told reporters the deal was a “major outcome not just for Japan but also for the future of the Asia-Pacific” region.

The final round of talks was delayed by negotiations over how long pharmaceutical corporations should be allowed to keep a monopoly period on their drugs.

The US wanted 12 years of protection, saying that by guaranteeing revenues over a long period it encouraged companies to invest in new research.

Australia, New Zealand and several public health groups argued for five years before allowing cheaper generic or “copy-cat” into the market.

They said a shorter patent would bring down drug costs for health services and bring lifesaving medicine to poorer patients.

Even though a compromise was reached, no definitive protection period was confirmed.

Speaking at a press conference following the deal, US Trade Representative Michael Froman hailed the deal as the first to set a period of protection for patents on new drugs, which he said would “incentivize” drug producers.

However, the Washington-based Biotechnology Industry Association said it was “very disappointed” by the reports that the agreement fell short of the 12-year protections sought by the US.

The auto industry was another area of intense negotiation with countries agonizing over how much of a vehicle had to be manufactured within the TPP countries in order to qualify for duty-free status.

Agriculture proved another sticking point with countries like New Zealand wanting more access to markets in Canada, Mexico, Japan and the US.

Canada meanwhile fought to keep access to its domestic dairy and poultry markets strictly limited. The issue and its impact on rural voters is particularly sensitive ahead of the federal election in two weeks time.