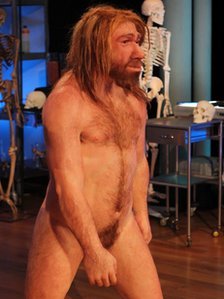

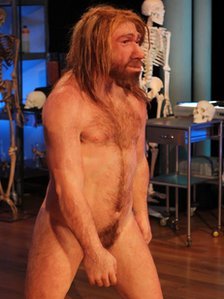

A team of scientists has created what it believes is the first really accurate reconstruction of Neanderthal man, from a skeleton that was discovered in France over a century ago.

In 1909, excavations at La Ferrassie cave in the Dordogne unearthed the remains of a group of Neanderthals. One of the skeletons in that group was that of an adult male, given the name La Ferrassie 1.

These remains have helped scientists create a detailed reconstruction of our closest prehistoric relative for a new BBC series, Prehistoric Autopsy.

La Ferrassie 1 is one of the most important discoveries made in the field of Neanderthal research.

His skull is the largest and most complete ever found. The discovery of his leg and foot bones was hugely significant, revealing to scientists that Neanderthals walked upright, contradicting previous research.

We now know that Neanderthals were stocky with strong arms and hands, and that they had large skulls – longer and lower than ours – with sloping foreheads and no chin.

But modern scientific research methods can now probe further to help us build a more accurate picture of the Neanderthals’ look and lifestyle. The scientists used these new approaches to reconstruct La Ferrassie 1.

But how do you go about reconstructing an entire lifelike body from a collection of 70,000 year old bones?

Much of La Ferrassie 1’s frame was intact, but the thorax, ribs, pelvis and some spinal pieces were missing.

US-based paleoartist Viktor Deak – who specializes in reconstructions and images of early man – filled in the gaps with copies of Neanderthal bones discovered at Kebara Cave in Israel in 1982. That dig uncovered a near-complete Neanderthal skeleton, missing just the cranium, right leg, and an area of the left leg.

A copy of the newly-complete La Ferrassie 1 was sent to a team of model makers in Buckingham. They pieced the bones together and set the finished skeleton in the correct, upright position.

The next stage was to add the Neanderthal’s muscles. But without a guide to follow, how could they be accurately replicated? Some detective work was required.

The La Ferrassie 1 skeleton was helpful in giving clues to assist the team of model makers, led by Jez Gibson-Harris.

He said that the size and texture of the bones gave an indication of the type of muscles the hominid would have had.

“You [could] see where the tendons would have attached. There were pretty big attachment points. You can see there were big muscles there.”

“[La Ferrassie 1 is] very strong looking, very stocky and well built. But really quite short.”

The bones also provided clues to the Neanderthal’s demanding and injury-prone lifestyle.

La Ferrassie 1’s arm bones are asymmetrical – the right is larger than the left. Bones change shape over a lifetime, so this led the scientists to look into the type of activities he may have carried out.

Dr. Colin Shaw of the University of Cambridge studied La Ferrassie 1’s flattened humerus.

“What you do to the bone through a lifetime causes adaptation, if it’s strenuous and repetitive enough,” says Dr. Colin Shaw.

The team studied the ways Neanderthals hunted their prey and carried out domestic chores, noting the impact those actions had on their bodies.

They concluded that they would have repeatedly stabbed their prey – the woolly mammoth – with spears, but that the really intense work would have been making garments to survive the cold climate.

A Neanderthal would have needed a new garment every year, which would have been made up of approximately five or six hides. They would have needed to scrape each hide for eight hours to make it wearable.

On the basis of this evidence La Ferrassie 1’s muscles, including those in the strong right arm, were reconstructed accordingly and layered on in clay.

Viktor Deak and Professor Alice Roberts leant their expertise to guide the model makers on other areas of the body.

“With Alice and with Viktor, and other scientists, commenting on the pose – ‘this muscle should be bigger on that side or the buttock should be smaller, or that should be longer’ – we built up the body structure in that way,” says Jez Gibson-Harris.

There were other, more obvious clues to La Ferrassie 1’s appearance contained within his remains. Many of his teeth were still attached and this helped Viktor Deak determine the shape of the face.

Studying teeth with state of the art technology is helping to unlock previously hidden secrets about the Neanderthals’ lifestyle. Powerful x-rays a thousand billion times stronger than a hospital x-ray machine can reveal the daily growth rate of teeth.

Studies comparing the age of teeth with the age shown by the rest of the skeleton suggest that Neanderthal children grew up faster than modern humans, and this may cast light on why our species survived and theirs did not.

The final stage of creating the replica was to add head and body hair. Here the team looked to previous research which revealed that many Neanderthals were redheads. La Ferrassie 1 was given red hair and a pale skin tone, suggestive of life in a northern climate.

Adding the hair was a painstaking process for the model makers, with each strand punched individually into the replica.

After two and a half months of meticulous work, La Ferrassie 1 was complete.

“It’s got a humanizing effect, putting the flesh on,” says Dr. John Hawks, an anthropologist from the University of Wisconsin, who is impressed by the result.

“Focusing on bone doesn’t give us the whole picture.”

The Neanderthal, La Ferrassie 1, is one of three recreations. Over six months the team also built Nariokotome boy, a member of the species Homo erectus, and one of our earliest prehistoric ancestors – an Australopithecus afarensis named Lucy.

It’s Chuck Norris!