Antarctic bivalves have surprised scientists who have discovered that the molluscs switch sex.

The reproduction of Lissarca miliaris was studied in the 1970s and the species was first described in 1845.

But their hermaphrodite nature had remained unknown until they were studied by scientists from the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK.

Researchers suggest the molluscs could switch between the sexes to efficiently reproduce in the extremely cold ocean.

The results are published in the journal Polar Biology.

“The previous reproductive study only looked at the large eggs and broods,” said PhD student and lead author Adam Reed.

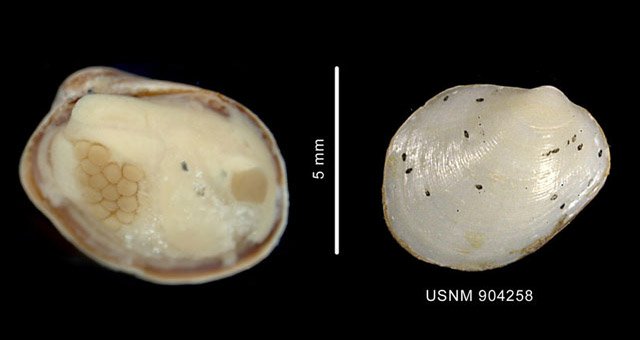

This earlier work showed how females brood their young for up to 18 months, from “large yolky eggs” to “fully shelled young”, and found that females can support as many as 70 young inside their hinged shell.

But concentrating on reproduction at a cellular level, Adam Reed and colleagues discovered that the eggs were actually present in males.

“Curiously, we found huge numbers of very small eggs in functional males, which appear to be far higher in number than an individual could brood throughout the life of the animal,” he said.

The team suggested that the bivalves reproduce as males while they are still in the “small” stages of development, switching to female organs once they are large enough to brood a significant number of eggs.

“At present the traits we describe are unusual for Antarctic bivalves, but in 10 years perhaps this will be common too,” said Adam Reed.

“Hermaphroditism is not necessarily uncommon in Antarctic bivalves, and with many species still to study there may be many more to describe.”

Brooding meanwhile is a relatively common reproductive trait in Antarctic invertebrates and has been linked to the extreme conditions.

“Brooding is common for small bivalves and has been discussed for many years in Antarctic biology,” said Adam Reed.

“Large yolky eggs that are brooded have much lower mortality than small planktonic larvae, but fewer are produced.”

He explained that in extremely cold environments, development is slowed down so feeding larvae becomes a more exhaustive task.

“Brooding reduces the need for long periods of feeding”, according to Adam Reed, making it a more efficient strategy for many Antarctic invertebrates including bivalves and echinoids.

The researcher suggested that the bivalves may be further maximizing their efficiency when it comes to reproduction.

“We also found that after males become female, the male reproductive tissue persists for a long time,” he said.

But for now, the bivalves can maintain their mystery because scientists are restricted to studying them during the months that staff is based at the British Antarctic Survey’s remote research station.

“Perhaps they may alternate their sex so they can continue to reproduce as males while brooding their young for 18 months?” Adam Reed theorized.

“The study highlights how much we do not know about some of the common invertebrates living in the Antarctic, and how much research there is still to do.”