The latest spacecraft in Europe’s long-running Meteosat series has just gone into orbit on an Ariane rocket.

It is now being manoeuvred into a position some 36,000 km above the Earth from where it can keep a constant watch on developing weather systems.

The spacecraft is the 10th Meteosat platform to go into service since 1977.

Its pictures will soon be feeding into the daily forecasts provided to the public by national meteorological agencies right across Europe.

“Verification and testing of the satellite’s systems will take two months. We expect to publish the first image on 6 August,” said Alain Ratier, the director-general of Eumetsat, the intergovernmental organization based in Darmstadt, Germany, that is charged with operating Europe’s weather platforms.

Thursday’s ascent to orbit from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana lasted some 34 minutes.

When it came off the Ariane’s upper-stage, the satellite was moving in a stretched ellipse around the planet, running from an altitude of 250 km out to 35,950 km.

Controllers at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), also in Darmstadt, will need to circularise that path in the coming 10 days.

They are targeting a geostationary observing position at zero degrees longitude, over the Gulf of Guinea on the Equator.

The satellite’s orbital speed will be matched to that of the Earth’s rotation, giving the platform’s sensors a constant view of Europe and Africa.

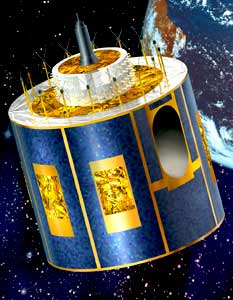

The Meteosats are now into the “second generation” (MSG) of design. This was introduced in 2002 to substantially increase the flow and quality of information to Europe’s forecasters. And Meteosat-10 is the third in that particular series (MSG-3).

As on the two antecedents, the primary instrument on Meteosat-10 is the Spinning Enhanced Visible and Infrared Imager, or Seviri.

It builds its pictures of evolving meteorological systems, line by line, by spinning across the field of view.

Data is acquired at 12 different wavelengths, tracing information such as cloud movement and changing temperature.

The two currently operational MSGs are used in distinct ways.

Meteosat-9 builds images of the entire field of view – a full Earth disc – in 15 minutes, while Meteosat-8 rapidly scans a smaller area covering Europe, to provide imagery in just five minutes.

This allows the weather agencies to better follow the development of powerful and potentially dangerous thunderstorms in Eumetsat member states.

“Assuming it comes through its commissioning, Metosat-10 is destined to image the full Earth disc, and that means Meteosat-9 will then take on the rapid scan role,” said Michael Williams, who heads Eumetsat’s control centre division.

“It’s possible Meteosat-8 may eventually be moved to the Indian Ocean to assume observing duties there, if that’s what our member states decide.”

This is a big year for Europe’s weather agencies. Not only are they getting a new geostationary Meteosat, they will also see the launch a new polar orbiting meteorological platform in September called Metop-B.

This spacecraft is arguably even more important than Meteosat-10. Metop will circle the Earth a few hundred kilometres above the ground, sampling the different layers in the atmosphere. Its data will feed into the numerical models that forecast likely weather conditions 24 hours to a few days ahead.

Its antecedent, Metop-A has made a major contribution to the improvement of these predictions, and Metop-B will maintain the data stream.

Eumetsat and its R&D partner, the European Space Agency, are also putting in place the 3bn-euro programme to succeed Metop at the end of the decade.

The Eumetsat Council has been meeting in Darmstadt to finalise details of the scientific instrumentation that will fly on the next-generation spacecraft.

Thursday’s gathering decided to include an Ice Cloud Imager (ICI) among the 10-instrument payload.

This will have been most keenly in the UK and in Spain where industrial consortia are very interested in building the instrument.

Britain’s Met Office has already been engaged in the design of prototype technology that can be tested on a plane.

ICI will see ice crystals forming in the high atmosphere, a phenomenon that influences the amount of solar radiation reflected back into space.

“This microwave imager will see ice crystals in cirrus clouds, which have a critical impact on the greenhouse effect,” said Alain Ratier.

“These crystals are semi-transparent and are therefore very difficult to see with Meteosat and infrared techniques. This instrument will be important for climate studies,” he said.

• Meteosats are spin stabilised spacecraft, and their visible and infrared imagers build up pictures line by line, south to north

• One platform – currently Meteosat-8, which was launched in 2002 – makes an image of Europe (A) every five minutes

• Meteosat-9 (B), launched in 2005, scans the full Earth disc. One image every 15 minutes comes down to controllers

• The satellites report the current status of the weather. Forecasters use this information as a check against modeled predictions