Venus is set to move across the face of the Sun as viewed from Earth in a more than six-and-a-half-hour transit, which starts just after 22.00 GMT on Tuesday.

The transit is a very rare astronomical phenomenon that will not be witnessed again until 2117.

Observers will position themselves in northwest America, the Pacific, and East Asia to catch the whole event.

But some part of the spectacle will be visible across a much broader swathe of Earth’s surface, weather permitting.

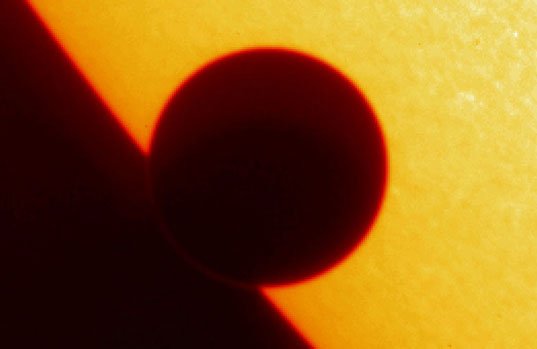

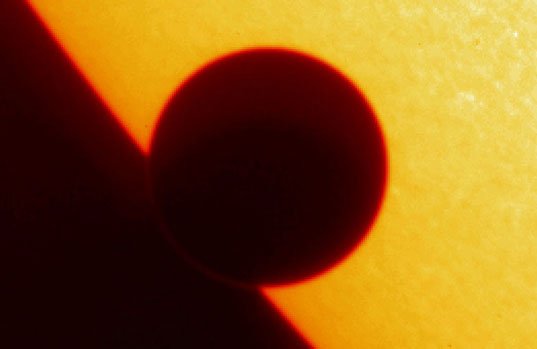

Venus will appear as a tiny black disc against our star, but no-one should look for it without the proper equipment.

Looking directly at the Sun with the naked eye, or worse still through an open telescope or binoculars, can result in serious injury and even blindness.

It is recommended people attend an organized viewing event where the transit will be projected on to a screen; or they can visit one of the many institutional internet sites planning to stream pictures.

Venus transits occur four times in approximately 243 years; more precisely, they appear in pairs of events separated by about eight years and these pairs are separated by about 105 or 121 years.

The reason for the long intervals lies in the fact that the orbits of Venus and Earth do not lie in the same plane and a transit can only occur if both planets and the Sun are situated exactly on one line.

This has happened only seven times in the telescopic age: in 1631, 1639, 1761, 1769, 1874, 1882 and 2004.

Once the latest transit has passed, the next pair will not occur until 2117 and 2125. Most people alive today will probably be dead by then.

The phenomenon has particular historical significance. The 17th- and 18th-Century transits were used by the astronomers of the day to work out fundamental facts about the Solar System.

Employing a method of triangulation (parallax), they were able to calculate the distance between the Earth and the Sun – the so-called astronomical unit (AU) – which we know today to be about 149.6 million km (or 93 million miles).

This allowed scientists to get their first real handle on the scale of things beyond Earth.

The first person to predict a transit of Venus – the 6 December, 1631, event – was Johannes Kepler, but he died before it occurred.

Jeremiah Horrocks, the young English astronomer, was probably the first to record the phenomenon when he and his friend, William Crabtree, made separate observations of the passage on 24 November, 1639.

By the time the transits of 1761 and 1769 came around, they had become major scientific events. Expeditions were despatched all over the globe to get the data necessary to calculate the AU.

One such expedition was undertaken by Captain James Cook, whose epic voyage in the Endeavour took in the “new lands” of New Zealand and Australia.

Modern instrumentation now gives us very precise numbers on planetary positions and masses, as well as the distance between the Earth and the Sun. But to the early astronomers, just getting good approximate values represented a huge challenge.

This is not to say the 2012 Venus transit will be regarded as just a pretty show with no interest for scientists.

Planetary transits have key significance today because they represent one of the best methods for finding worlds orbiting distant stars.

NASA’s Kepler telescope, for example, is identifying thousands of candidates by looking for the tell-tale dips in light that accompany a planet moving in front of its host sun.

These planets are too far away to ever be visited by spacecraft, but scientists can learn something about them from the way the background star’s light is affected as it passes through the planetary atmosphere.

And observing a transiting Venus, which has a known atmospheric composition, provides a kind of benchmark to support these far-flung investigations.

But Venus itself will come in for scrutiny. Scientists will be using the event to probe the middle layers of the Venusian atmosphere – its mesosphere.

They will be looking for a very thin arc of light, called the aureole, which can only be seen when Venus appears to just touch the edge of the Sun’s disc.

The brightness and thickness of the aureole depends on the density and temperature of the atmospheric layers above Venus’s cloud tops.

Observations of the aureole will be combined with data from Europe’s Venus Express spacecraft in orbit around the planet to provide information on high-altitude winds.

The Venusian atmosphere experiences super-rotation. That is – the whole atmosphere circles the planet in four Earth days, on a body that turns around just once in 243 Earth days.

[youtube p1aAG2TUNY0]