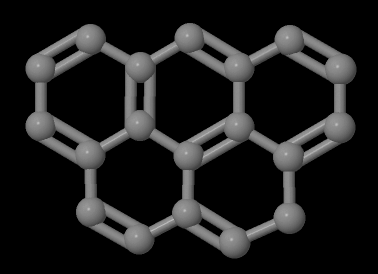

An international research team has succeeded in taking an amazing image of a newly synthesized molecule called olympicene.

The molecule – just over a billionth of a metre across – gets its name because its five linked rings resemble the Olympic symbol.

It was first made by collaborators at the University of Warwick in the UK.

They teamed up with IBM researchers, who in 2009 pioneered the technique of single-molecule imaging with its non-contact atomic force microscopy.

The team, based at IBM Research Zurich, announced its first success with a molecule called pentacene, five linked hexagonal rings of carbon all in a line.

It was Professor Graham Richards CBE, former head of Oxford University’s chemistry department and member of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) council, who first conceived of the idea to create a more Olympic-themed molecule along the same lines.

“I was in a committee meeting of the Royal Society of Chemistry where we were trying to think of what we could do to mark the Olympics,” said Prof. Graham Richards.

“It occurred to me that the molecule that I had drawn looked very much like the Olympic rings, and it had never been made.”

University of Warwick researchers Anish Mistry and David Fox undertook the task of developing a chemical recipe for the molecule, and took preliminary images of it using a technique called scanning tunnelling microscopy.

But no approach gives such detailed images of single molecules as non-contact atomic force microscopy, in which a single, even tinier molecule of carbon monoxide is used as a kind of record needle to probe the grooves of molecules with unprecedented resolution.

The images show linked ring structures that are reminiscent both of the Olympic rings and a great many compounds made from rings of carbon atoms, including the “miracle material” graphene.

However, Prof. Graham Richards hopes that olympicene’s greatest contribution to chemistry is to bring more students into it.

“Molecules of this nature could conceivably have commercial use, but my own feeling is that above all we want to excite an interest in chemistry provoked by the link with the Olympics,” he said.