Oh Kil-nam, a retired South Korean economist, says his life was ruined by his decision to defect to North Korea.

Oh Kil-nam, 70, still does not know the fate of his wife and daughters – either dead or imprisoned in a labor camp.

In 1985, North Korean agents approached Oh Kil-nam and suggested he defect.

The agents offered him an important job working as an economist for the North Korean government and promised to provide free treatment for his wife’s hepatitis.

Oh Kil-nam took the offer seriously. He had just completed his PhD in Germany on a Marxist economist. Back at home in South Korea, Oh Kil-nam had been active in left-wing groups opposed to the country’s authoritarian regime.

His wife Shin Suk-ja was horrified by the idea of going to the North and opposed it from the start.

“Do you know what kind of place it is?” she asked.

“You have not even been there once. How can you make such a reckless decision?”

But Oh Kil-nam replied that the Northerners were Koreans too – they “cannot be that brutal”, he told her.

So at the end of November 1985, Oh Kil-nam, his wife and two young daughters travelled via East Berlin and Moscow to Pyongyang.

When they arrived at Pyongyang airport, Oh Kil-nam began to see he had made a mistake in coming. Communist party officials and children clutching flowers were there to meet them. But despite the cold of a North Korean December, the children were not wearing socks and their traditional clothes were so thin that they shivered.

“When I saw this I was really surprised and my wife even started to cry,” he said.

Communist party officials drove Oh Kil-nam and his family to what they described as a guest house. The building was inside a camp in the mountains and guarded by soldiers. There was no treatment for Shin Suk-ja’s hepatitis and no job for Oh Kil-nam as an economist. Instead, for several months, North Koreans indoctrinated them in the teachings of The Great Leader Kim Il-sung, the founder of the current regime.

Oh Kil-nam and his wife began working for a North Korean radio station.

“My wife began as a broadcaster but she was not able to carry on for long. Her health had deteriorated and at the same time she was quite critical of the North.”

Oh Kil-nam was less independent. “I began to read scripts based on party directives – in the end, I was like a parrot.”

While he was there Oh Kil-nam came across South Koreans who had been abducted, including two air stewardesses and two passengers from a Korean Air Lines flight that had been hijacked by North Koreans in 1969.

Oh Kil-nam was approached to go on a mission abroad. He was to be based in the North Korean embassy in Copenhagen, from where he could do what had been done to him – lure South Korean students in Germany to the North Korean embassy.

When Shin Suk-ja heard about the plan she was furious.

“I remember the two of us talking about it softly under the blanket. I told my wife that by fulfilling this mission, we would preserve our livelihood in North Korea. But she slapped me in the face.”

His wife said they would have to pay the price for his mistakes – he could not entrap others.

“She told me I had to find a way to escape when I got to Europe, that there would be a way to rescue the family.”

On arriving at Copenhagen airport, Oh Kil-nam managed to escape from North Korean control. “I approached the immigration desk. I had a little piece of paper on which I had written: HELP ME. I explained that the passport they were seeing was not my real passport, that my real name was Oh Kil-nam, and that my real passport had been confiscated in North Korea.”

After two months in jail in Denmark, the Danish authorities sent Oh Kil-nam to Germany. There he tried to free his family, but with no luck.

“My biggest mistake was not to approach the German Foreign Ministry directly.”

For Shin Suk-ja and her two daughters, Oh Kil-nam’s defection was catastrophic. They were taken to Yodok concentration camp, where the North Korean government imprisons its enemies. The conditions in this slave labor camp are reportedly as bad as anything in Nazi Germany or Stalin’s Gulag.

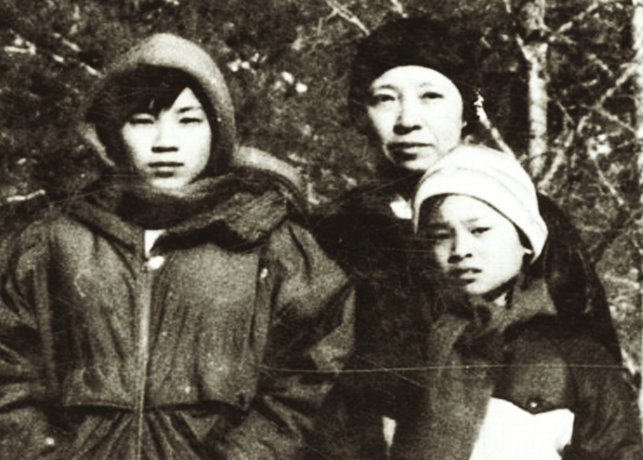

For a time, Oh Kil-nam heard nothing about the fate of his family. Then in February 1991 he managed to get six photographs of his wife and daughters and a tape cassette with a message from them.

“On the tape my daughters were telling me how much they missed me and my wife was saying that perhaps it would be OK for me to come back now.”

Oh Kil-nam suspected a trap. “North Korea was trying to stop me from heading back to South Korea because I had experience of working in its propaganda division. I knew a lot of its secrets, including the fact that many people from South Korea, who were kidnapped and taken to the North, were working there.”

But nonetheless the realization that he could not get back in touch with his family was devastating.

“By that time I had completely given up. My whole body was just broken down.”

In 1992, Oh Kil-nam returned to South Korea. “I felt that my death was not far away. I just wanted to be close to my brother and my sister on my death bed.”

Oh Kil-nam did not die but nor has he ever heard from his wife and daughters again. He does not know whether they are alive or whether they died in the prison camp.

“I do feel that I may be able to meet my family again, but it is just a hope, a glimmer of hope inside a dark tunnel.

“I hope there will come a day when I can meet my family again, hug them and embrace them, and cry tears of happiness. If it does happen it will be the happiest day of my life.”