Multituberculates, a group of rodent-like mammals that existed for approximately 120 million years, survived after dinosaur extinction because they were adapted to eating flowering plants, say scientists.

The “mass extinction event” which wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago is thought to have been caused by an asteroid or volcanic activity.

Once the dinosaurs were no more, the rodent-like multituberculates continued to prosper.

Now scientists have learned the secret of multituberculates’ success.

The mammals were adapted to eating angiosperms, flowering plants that only started to appear around 140 million years ago.

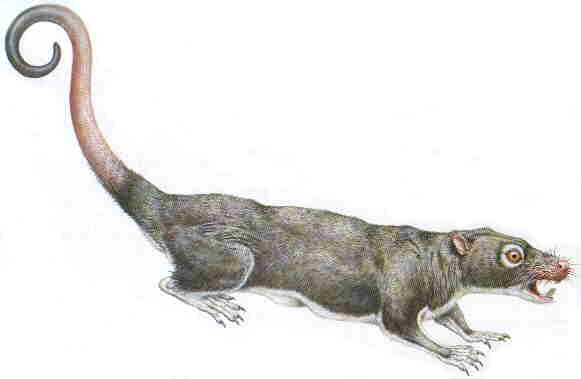

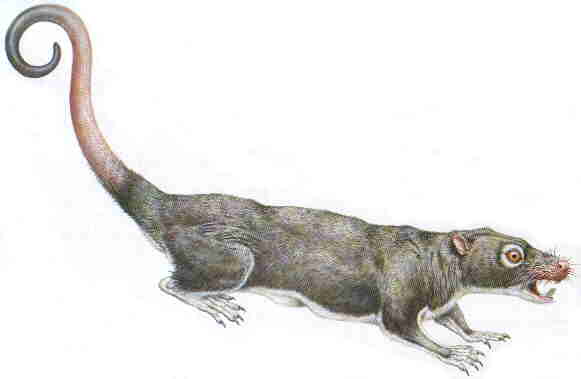

After the arrival of angiosperms, the multituberculates evolved into a diverse group of animals ranging in size from that of a mouse to a beaver.

They only eventually vanished from the Earth some 34 million years ago after losing out to other mammals such as primates, hoofed species and rodents.

Multituberculates were distributed across the world and more than two hundred species are known, some as small as the tiniest of mice and the largest the size of beavers.

Some, such as Lambdopsalis from China, lived in burrows like prairie dogs while others, such as the North American Ptilodus, climbed trees as squirrels do today.

Multituberculates are the only major branch of mammals to have become completely extinct, and have no living descendants.

Although not known to many people, they have a 100 million-year fossil history, the longest of any mammalian lineage.

The narrow shape of their pelvis suggests that, like marsupials, multituberculates gave birth to tiny, undeveloped pups that were dependent on their mother for a long time before they matured.

Although there are some spectacular multituberculate specimens from Mongolia, many of these unique teeth have been found in North America.

Scientists examined teeth from 41 multituberculates kept in fossil collections around the world.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning similar to that used in hospitals was used to create high resolution 3D images which were then analyzed.

The researchers found the multituberculates had a complex array of teeth. Those at the front were sharp and blade-like, while the back teeth developed numerous bumps and cusps ideal for crushing plant material.

“These mammals were able to radiate in terms of numbers of species, body size and shapes of their teeth, which influenced what they ate,” said Dr. Gregory Wilson, from the University of Washington, who led the research published online in the journal Nature.

“If you look at the complexity of teeth, it will tell you information about the diet. Multituberculates seem to be developing more cusps on their back teeth, and the blade-like tooth at the front is becoming less important as they develop these bumps to break down plant material.”

The research involved determining which direction various patches of tooth surface were facing. More complex teeth have more patches.

Carnivores have relatively simple teeth with perhaps 110 patches per tooth row because their food is easily broken down.

In contrast, some multituberculates had up to 348 patches per tooth row.