Researchers from Austin, Texas, have “cloaked” a 3-D object, making it invisible from all angles, for the first time.

However, the demonstration works only for waves in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

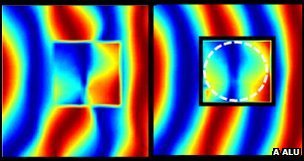

The demonstration uses a shell of what are known as plasmonic materials; they present a “photo negative” of the object being cloaked, effectively cancelling it out.

The idea, outlined in New Journal of Physics, could find first application in high-resolution microscopes.

Most of the high-profile invisibility cloaking efforts have focused on the engineering of “metamaterials” – modifying materials to have properties that cannot be found in nature.

The modifications allow metamaterials to guide and channel light in unusual ways – specifically, to make the light rays arrive as if they had not passed over or been reflected by a cloaked object.

Previous efforts that have made three-dimensional objects disappear have relied upon a “carpet cloak” idea, in which the object to be cloaked is overlaid with a “carpet” of metamaterial that bends light so as to make the object invisible.

Andrea Alu and colleagues at the University of Texas at Austin have pulled off the trick in “free space”, making an 18 cm-long cylinder invisible to incoming microwave light.

Light of all types can be described in terms of electric and magnetic fields, and what gives an object its appearance is the way its constituent atoms absorb, transmit or reflect those fields.

Prior metamaterial approaches sidestep these effects simply by channeling light around an object, using carefully designed structures that bounce light in prescribed way, like a pinball machine.

By contrast, plasmonic materials can be designed to have effects on the fields that are precisely opposed to those of the object.

“What we do is different; we realize a shell that scatters [light] by itself, but the interesting point is that if you combine the shell with the object inside, the two counter out and the object becomes completely invisible,” said Prof. Andrea Alu.

The plasmonic material shell is, in essence, a photo-negative of the object being cloaked.

As a result, the cloak has to be tailored to work for a given object. If one were to swap different objects within the same cloak, they would not be as effectively hidden.

But the success with the cylinder suggests further work with different wavelengths of light is worth pursuing: “It’s a real object standing in our lab, and it basically disappears,” said Prof. Andrea Alu said.

However, the idea is unlikely to work at the visible light part of the spectrum.

Prof. Andrea Alu explained that the approach could be applied to the tips of scanning microscopes – the most high-resolution microscopes science has – to yield an improved view of even smaller wavelengths of light.

Ortwin Hess, professor of metamaterials at Imperial College London, said the work was a “very nice verification that this approach works”.

“There are some limits on where these things can be applied, but nevertheless it’s really, really interesting and fundamental indeed,” he said.

Prof. Ortwin Hess explained that for future applications, plasmonic materials could be combined with the structured metamaterials idea already in development elsewhere. Light can be channelled where it needs to go, or its effects undone, as need be.

Cloaking in visible light, hiding more complex shapes and materials – that is, a cloak of Harry Potter qualities – remains distant, but Prof. Andrea Alu pointed out that the steps in the meantime will be put to use.

“There is still a lot of work to do,” he said.

“Our goal was just to show this plasmonic technique can reduce scattering from an object in free space.

“But if I had to bet in five years what kind of cloaking technique might be used for applications, for practical purposes, then I would say plasmonic cloaking is a good bet.”