A senior CERN physicist from Switzerland has announced this afternoon firm evidence for the existence of the elusive Higgs Boson, or God particle.

Although the signal doesn’t meet strict scientific standards for a “full scientific discovery”, it’s still enough for researchers at CERN’S Large Hadron Collider (LHC) to predict a discovery next year.

Two separate teams of scientists have been running independent experiments in secret from each other in order to improve the veracity of the results with the team leader of one, Fabiola Gianotti, proclaiming that they believe they’ve found signs of the Higgs boson in the past year.

“We have built a solid foundation for the months ahead,” Fabiola Gianotti said.

However, CERN was cautious: “The main conclusion is that the Standard Model Higgs boson, if it exists, is most likely to have a mass constrained to the range 116-130 GeV [a unit of energy equal to billion electron volts] by the ATLAS experiment, and 115-127 GeV by CMS.

“Tantalizing hints have been seen by both experiments in this mass region, but these are not yet strong enough to claim a discovery.

“Higgs bosons, if they exist, are very short lived and can decay in many different ways. Discovery relies on observing the particles they decay into rather than the Higgs itself. Both ATLAS and CMS have analyzed several decay channels, and the experiments see small excesses in the low mass region that has not yet been excluded.”

The upshot of the experiments, therefore, is that researchers believe the Higgs is fairly lightweight, which could lead to more exciting discoveries, according to New Scientist’s Lisa Grossman.

Lisa Grossman wrote: “A Higgs of this mass, about 125 gigaelectronvolts, would blast a path to uncharted terrain. Such a lightweight would need at least one new type of particle to stabilize it.”

When looking at results, the scale of certainty used by researchers is the sigma, something peculiar to particle physics.

Researchers need a five-sigma level of certainty to make a bona-fide formal discovery, which means there’s only a one in a million chance that the result is a statistical error.

Scientists only formally acknowledge an experiment’s results if they hit a three sigma level, which means there’s only a 1 in 370 chance of them being a fluke.

The sigma probabilities announced today for the Higgs hunt have not been combined, but the overall ATLAS result was 2.3.

Before the press conference began, CERN described the room as “full to the rafters. People would hang from the lamps if the security guards would let them”.

The Higgs boson is regarded – by those who know about such things – as the key to understanding the universe. Its job is, apparently, to give the particles that make up atoms their mass.

Without this mass, these particles would zip though the cosmos at the speed of light, unable to bind together to form the atoms that make up everything in the universe, from planets to people.

The Higgs boson’s existence was predicted in 1964 by Edinburgh University physicist Peter Higgs. But it has eluded previous searchers – so much so that not all scientists believe in its existence.

The hunt for the Higgs boson was one of the LHC’s major tasks.

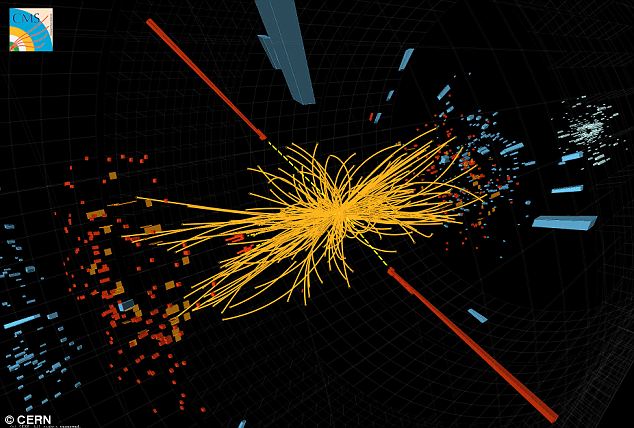

The collider, housed in an 18-mile tunnel buried deep underground near the French-Swiss border, smashes beams of protons – sub-atomic particles – together at close to the speed of light, recreating the conditions that existed a fraction of a second after the Big Bang.

If the physicists’ theory is correct, a few Higgs bosons should be created in every trillion collisions, before rapidly decaying.

This decay would leave behind a “footprint” that would show up as a bump in their graphs.

The CMS – or Compact Muon Solenoid – is a 13,000-ton machine that sits 330 feet underground, while the ATLAS, at 148 feet long and 82 feet high, is the biggest detector ever constructed.

From the Big Bang to the 1960s

The existence of the Higgs boson was put forward in the 1960s to explain why the tiny particles that make up atoms have mass.

Theory has it that as the universe cooled after the Big Bang, an invisible force known as the Higgs field formed.

This field permeates the cosmos and is made up of countless numbers of tiny particles – or Higgs bosons.

As other particles pass through it, they pick up mass.

Any benefits in the wider world from the discovery of the Higgs boson will be long term, but they could be felt in fields as diverse as medicine, computing and manufacturing.

Experts compare the search for the Higgs boson to the discovery of the electron.

The idea of the electron – a subatomic particle – was first floated in 1838, but its presence was not confirmed for another 60 years.

A century on, the electron’s existence underpins modern science. Our understanding of it is critical to the development of technology from television and CDs to radiotherapy for cancer patients